Fiction

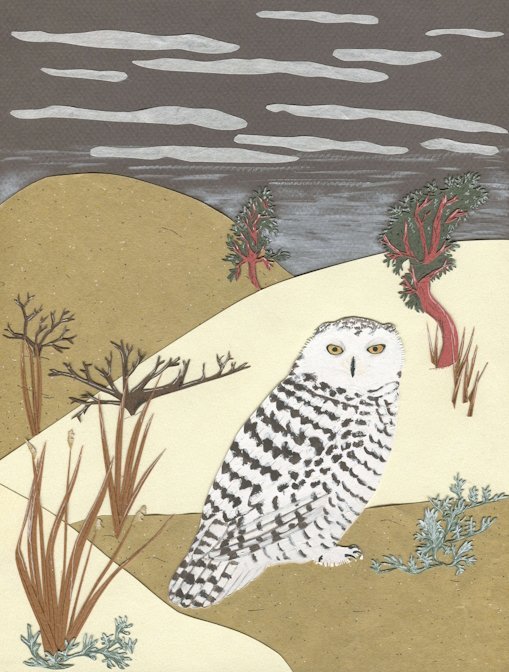

SPRING 2024Don’t Look at the Owls

by AUDACIA RAY

There are two things about feeding the owls that the ranger made sure Robin understood on day one: there’s a freezer full of dead rats and mice that she’d have to get very comfortable dealing with, and owls feel threatened by eye contact, especially in small spaces. She was not allowed to look directly at them. Robin felt vaguely threatened by eye contact too, so this second directive felt not only fine, but like a relief.

Robin had first learned of the raptor center in fifth grade, when she was ten years old, when her school held a special assembly where the students got to see these incredible birds up close. Two rangers in green uniforms and firmly shaped hats wore thick gloves and the birds gripped onto them, flexing their talons, blinking their round eyes. Robin was captivated. The rangers talked about how each of the birds had been injured, that they tried to help them heal with weeks or months of physical therapy that toned the birds’ muscles for flight, a rotating perch game to help them relearn balance and stability, and practice flights in local fields uninterrupted by power lines and roadways (a real challenge to find). Despite their efforts, some birds could not be released again: the bald eagle who lost her foot after getting tangled in discarded fishing line, the red-tailed hawk who had been hit by a car when she dipped down off a power line to snag prey off the shoulder of a busy road and could now fly only short distances, the barn owl who had survived eating a poisoned rat but had permanent balance issues and cognitive impairment as a result.

At ten Robin felt more like a frightened rabbit than a bird of prey. She didn’t want to rip anything apart, she didn’t want to clutch onto small bleeding warmth as the life ebbed out. She was easily startled, protective of her softness. But she respected the birds, the pattern of the females being larger than the males, the way the raptor center birds regarded the sky while their disabled bodies carried the knowledge that they’d never freely soar there again. While other kids like her had cats and dogs whose fur they could cry into and into whose ears they could whisper the secrets of their genders, Robin’s parents forbid pets, said animals were dirty and expensive. Her parents’ steadfast refusal at her many requests to bring an animal into her life felt like she was being denied comfort. As she grew older and more fascinated with watching wild creatures, she appreciated the kinds of animals that flourished best in the wild, uncontained, not available for petting or snuggling.

At fifteen Robin’s body had started to change later than the other girls, and she loathed what it was becoming: angles sharpening, voice box cracking. Her parents had denied her the soft comfort of an animal companion when she was younger, then they denied her the hormone blockers she’d campaigned for and the estradiol she needed to steer her into the correct version of puberty, saying that she was too young to know anything real about herself. They said that when she lived on her own, she could do as she pleased. While she lived in their house, no son of theirs would suspend the animation of masculinity and then reroute. What they didn’t understand was that as masculine features began to emerge, she was more at risk of being torn apart by her own hand or the talons of another. She moved through the halls at school and home with the cadence of a prey animal, expecting violence.

For meals and family meetings, Robin positioned herself at the honey orange kitchen table so that she could look out over the backyard instead of at her parents’ faces. During a tense conversation with her parents early in her sophomore year, as they were once again denying her reality, she looked past them and out the window to the birds. Her namesake bird, the robin, hopped around the grass. Her mother saw the bird as a predictor of spring, but she knew that these thrushes didn’t all migrate south in the winter. Rather, they teamed up into small flocks and searched the countryside for winter berries to share. Their togetherness in lean times helped them all survive; they were collaborating rather than competing. She dissociated from whatever her parents were saying about her gender, their control over her body as the people who made her, her presumptive homosexuality.

As she stared out the window, she saw a chaotic clash of feathers as a hawk dropped down out of the sky, wings folded back crooked as it dove, righting itself at the last moment to bury its talons into the body of a rabbit. The hawk stood on its quarry, yellow feet enmeshed in the soft meat of the mammal, alertly surveying the yard for competitors. Then it flexed its talons and lifted the limp brown body up, carried it to the railing of the back deck, less than twenty feet from where Robin sat. It adjusted the position of its prey and then dug its curved beak into the rabbit’s belly, split it open, and began pulling out steaming ribbons of intestines. She observed the hawk closely as it eviscerated the rabbit with steady resolve. As her parents droned on, a small spark lit up in her brain as she formed the thought that conscious violence and the need to survive were different things. Robin thought back to the birds of prey assembly at school all those years ago and decided that she would look up that raptor center and ask to volunteer with them.

The hair on the back of Robin’s neck prickled when she felt the wing-wind of a great horned owl swoop powerfully close to her hair. She kept her head down as she heard the owl alight on a perch across the enclosure, the soft thud of its three-pound body. Three months into volunteering, Robin was getting the hang of caring for creatures that she came very close to but would neither touch nor look at directly. Inside the enclosure, she’d scour the ground for owl pellets, compressed ovals of hair and bones, the undigestible pieces of the owl’s diet. Though the bones were often crunched up after what they’d been through, sometimes she’d pluck a whole rat skull from the pellets; a found treasure. She’d dissected owl pellets in middle school and the rescue welcomed her idea to sell the pellets to raise money for the feeding and maintenance of the birds, and she’d started collecting pellets in a bin, though sometimes she picked them apart herself. She was planning a presentation on owl diets for her science fair project, and then would use that to pitch the idea of creating the rescue-to-high-school-science-lab pipeline for the pellets she’d stashed.

Though she’d been immediately captivated by the refuse of the owls’ diet, it had taken her longer to get used to the whole rats in the state they were in before the owls ate them. They arrived flash frozen in shrink-wrapped groups of five, like supermarket meat on a yellow Styrofoam tray. The rescue had a walk-in freezer expressly for the purpose of storing the whole adult rats for the bigger birds, along with mini glaciers of frozen pinky mice for the kestrels and screech owls. The pinky mice were creepy, as they were fleshy lumps of nude baby mice that had to be chipped off the ice block with a hammer. The adult rats defrosted in industrial sinks, became drippy and limp as she used gloved hands to lift them up by their tails and place them into buckets to carry around and distribute to the owls. The chunks of pinky mice went directly into the bucket; they thawed and separated as Robin made her rounds. The birds at the rescue, whether they were permanent residents or there were plans to release them, had their instincts dulled by dining on pre-killed rats, but they were too likely to starve or suffer further injury if they’d had to pursue live prey inside chain-link walls.

There were three great horned owls in this particular enclosure, the first on her feeding route, and Robin was getting to know them by listening and sensing where they were in the space. Though their flights were silent, so she could be surprised by the draft of a swoop as she had been this afternoon, the birds were very chatty and vocalized widely and frequently. In her early days of volunteering at the rescue, she had spent her evenings searching for owl hoots on YouTube and learning to tell them apart. The great horned owls sounded most like a cartoon owl, booming whoo-hoooting away. But she’d loved learning that owls made a much wider range of sounds beyond the hoot, and the hoot itself could be a sexy croon or percussive warning; their sounds were part of their individual personalities. The two larger, older birds had gotten used to Robin and had shifted from squawking at her—sounds that made her think more of a coyote than a bird—to making conversational chittering sounds when she came into the enclosure, rapid staccato sounds as close to tweeting as these serious birds could get.

The smallest of the three had been in a tree that got chopped down; its nestmates had been killed on impact. It, like the other birds, was in the raptor center overwhelmingly because of the negative impacts that human choices had on their environment. The owlet was an angry, grieving ball of fluff when it came to the rescue. It had pretty relentlessly made screeching food-begging calls in its smaller enclosure the first few weeks, but now that it had been introduced to the two permanent residents, it was starting to imitate the more friendly chittering of the older owls. Its wings beat an unsteady rhythm as it figured out the mechanics of flying. Robin heard the clang and bounce as it awkwardly landed on the chain-link fence of the enclosure. It clacked its beak, a sign of displeasure that Robin didn’t want to anthropomorphize too much, but to her it did seem that the owlet was embarrassed by its lack of control over its awkward teenage body. She smiled to herself. Before she began dedicating her weekends to the raptor center, she thought of all birds, but especially birds of prey as elegant, precise creatures. But she was learning that they made their miscalculations, had awkward landings, missed their targets more often than not.

This fledgling owlet was still eating largely pinky mice, little bald creatures that had never fully opened their eyes before they were flash frozen. Robin had brought her bucket of thawed rodents of varying sizes with her, and she carefully unlatched the gate, stepped into the enclosure and decorated the floor with them. The fledgling was getting bolder, and it landed in a heap several feet away from her, gripping a pinky mouse in one talon. She didn’t look but knew its nictitating membrane passed a diagonal shield over its eyes. In her peripheral vision she watched the owlet throw its head back and chug the mouse down its throat. Robin listened for the older owls, let her skin stay sensitive to the movement of the air. They had made friendly welcoming noises but were biding their time until she was gone and they could do their facsimile of a hunt in privacy. The fledgling remained on the ground, ruffled its feathers. Done with this feeding, she lifted the latch on the gate to leave, and faster than she thought a flying creature could sprint, the owlet hopped through the slightly open gate and pounced on something moving in the grass. A garter snake. Its hunting instinct had taken both of them by surprise. She laughed as the young owl looked back over its shoulder at her, actively seeking out her face for her reaction and perhaps approval. The young bird chittered a rippling wave of vocalizations, the snake threaded in its talons.

Audacia Ray

Audacia Ray (they/she) is a queer nonbinary person who spends their time in Brooklyn and the Catskill Mountains. A Tin House alum who has published fiction and essays in Necessary Fiction, The Rumpus, Litro Magazine, Penumbra, and Superstition Review, they also serve their LGBTQ community as Director of Community Organizing and Public Advocacy at the New York City Anti-Violence Project. Their website is audaciaray.com.