Visual

SPRING 2022Robert Martin

Female Red-Winged Blackbird with Red Epaulets

Charcoal, acrylic, and oil on mounted paper in reclaimed frame, 5 x 7 in., 2021

Occasionally, female red-winged blackbirds will develop red epaulets, widely understood to be a feature only males of the species are “supposed to” possess. The coloration does not seem to impede on breeding success or other normal functions. The females simply exist. I understand this as an instance of “queerness” in nature, by which I mean our heteronormative understandings fall short of comprehending the species’ full spectrum of existence.

Queerness is not absent from the American hinterland. In fact, I see it everywhere. The trouble comes from a lack of acknowledgement, and the bleeding of human heteronormative perceptions over the natural, fluid environment. I am using the visual language of ruralcore art to communicate queer themes, identities, and storylines within middle America in a way that is legible to an unaddressed community. I am interested in generating conversation over critique; between the queer community and rural America, between the canonized fine arts and the commodified wildlife arts, across wealth brackets and beyond a gender binary. Here, I illustrate my journey in employing wildlife as symbolism, and ultimately, the importance of shining light on the queerness that exists around us.Marsh Portrait

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 31.5 x 71.75 in., 2021

As an undergraduate student at the University of Wisconsin Stout, I began producing work that reflected the various facets of my identity—as a homosexual, as a Midwesterner, as a Catholic-raised agnostic—with intentional nuance. I permitted myself to speak subtly of homosexuality under a perceivable guise of wildlife art. The red northern cardinal was used as a stand-in for the flamboyant, flashy male I understood myself to be. In my BFA thesis work, a pairing of bright red cardinals communicated homosexual relations. Following the completion of my degree, I was uncertain if I felt comfortable continuing to employ male birds as symbols of my own sexuality. I questioned my gender identity, and found more assurance in “queerness” over “homosexuality.”Jacket Portrait (Martin Ross) with Red-winged Blackbird Pair

Acrylic and oil on stretched canvas in reclaimed frame; oil and acrylic on slip cast porcelain with custom oak shelf, 16 x 20 in., 2021

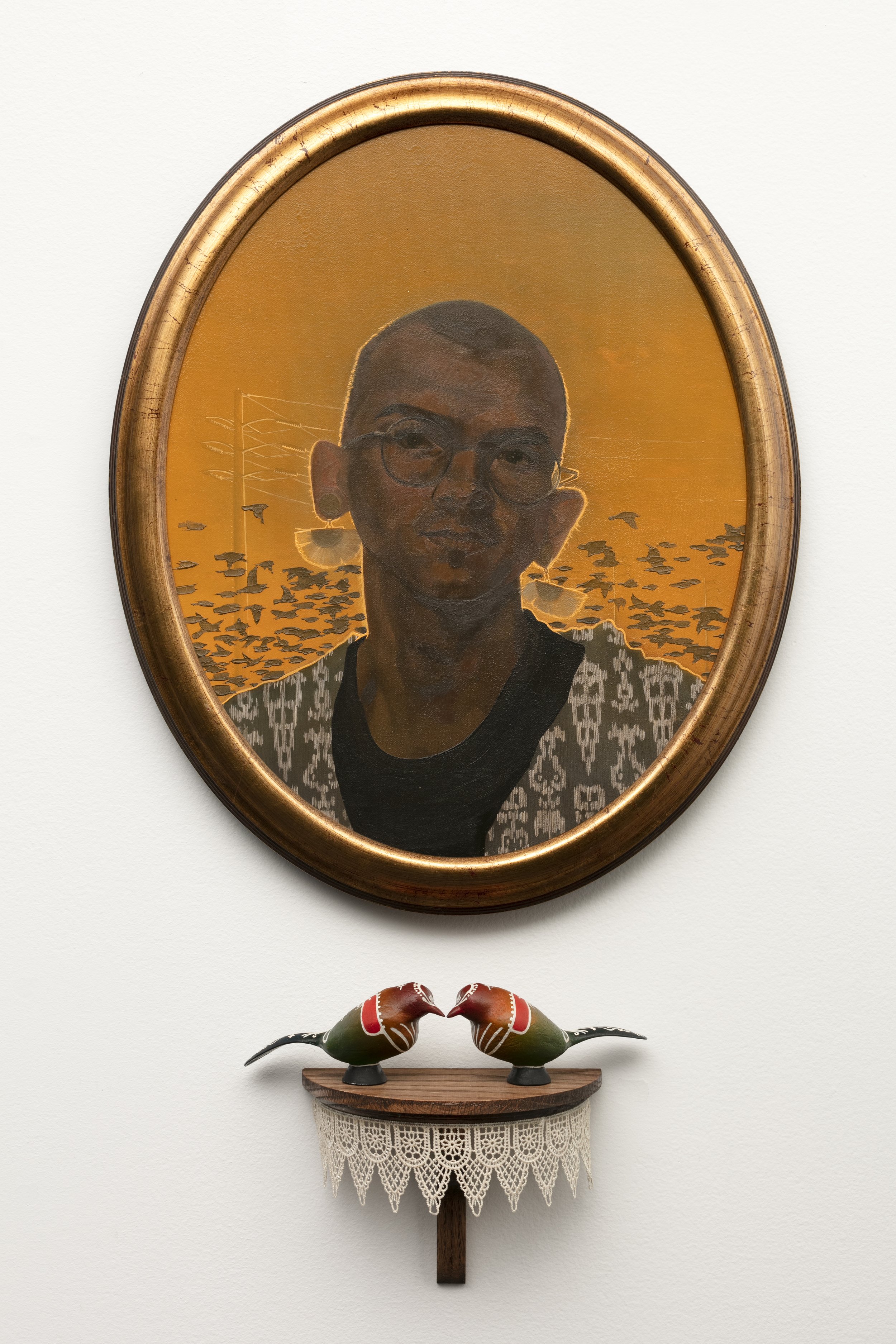

Jacket Portrait (Robert Martin) with Red-winged Blackbird Pair

Acrylic and oil on stretched canvas in reclaimed frame; oil and acrylic on slip cast porcelain with custom oak shelf, 16 x 20 in., 2021

In January of 2019, the winter after I came out as nonbinary, articles began circulating featuring a northern cardinal photographed by Shirley and Jeffrey Caldwell of Erie, Pennsylvania. The headlines read like flyers for a circus sideshow: “Bizarre Half-Male, Half-Female Bird Discovered In Pennsylvania” on Forbes; “Rare half-male, half-female cardinal spotted in Pennsylvania” for National Geographic; “This Bird’s Body Is Half Male, Half Female. So Is Its Brain” in Live Science; “A Rare Bird Indeed: A Cardinal That’s Half Male, Half Female” in the New York Times. Through the sensationalism, I found a grounding sort of comfort after being made aware of this gender deviation. While the press painted it as a sort of freak of nature, this species was, once again, providing me the external validation I sought.Valerie Sharing Seeds

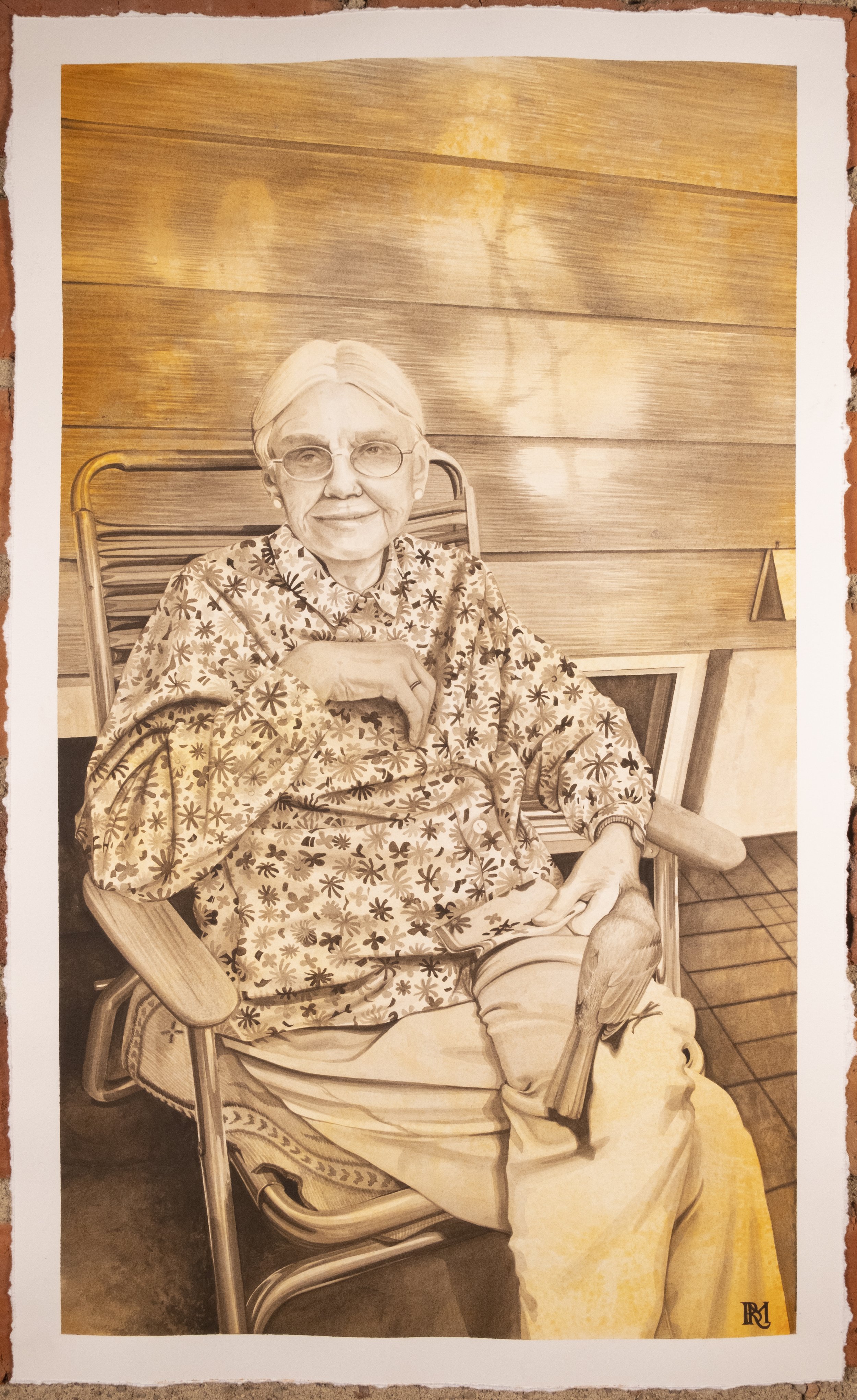

Watercolor on paper, 20.5 x 12.5 in., 2022

This is a recent depiction of my grandmother, Valerie, sharing seeds with a male northern cardinal. The depiction is created in recognition of the interest and care for birds (and nature) instilled in me by my family.

In growing up in the Northwoods of Wisconsin, I’ve observed queerness in nature, even before I fully comprehended human queerness, but this was the first instance wherein the difference felt like a true reflection of my own identity. Bilateral gynandromorphism isn’t exactly congruent to human non-binariness. As Michelle Starr writes for Science Alert, the northern cardinal is exhibiting “a type of genetic chimerism, whereby a single animal has more than one set of DNA. More specifically, it’s a type of tetragametic chimerism, so-named because it involves four (tetra) gametes—two sperm and two ova.” Here, the “split” happens because two fertilized ova fuse together early on during development, becoming one blastocyst or zygote. Still, the bird provided a visual representation for my liminal feelings around gender identity: a concrete symbol in nature.Robert Martin

Robert Martin earned their BFA in studio art (drawing and sculpture) from the University of Wisconsin Stout in 2017 and their MFA in studio practices (painting and drawing) at the University of Colorado Boulder in 2012. They have exhibited works at Bermudez Projects in Los Angeles, 1969 Gallery in New York, GOCA in Colorado Springs, Sierra Arts Gallery in Reno, IDS Tower in

Minneapolis, the Valley in Taos, and along Colorado’s Front Range. They were a 2020 Rough Gems Curator at Union Hall in Denver and a 2019 NEST Grant recipient at CU Boulder, and their work was featured in UW Stout’s 2017 Journal of Student Research. Most recently, in the fall of 2021, Martin was awarded the New American Paintings Emerging Artist Grant, and they will be a featured artist in the Denver Art Museum’s 2022 Untitled series this June. Martin currently volunteers on the board of the newly formed Rural Midwest Artists Cooperative, is a program coordinator at Union Hall in Denver, and teaches in the Foundations Department at the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design.