Room for Craft

DECEMBER 2019: SARAH HEADYPhoto by Joseph Crockett

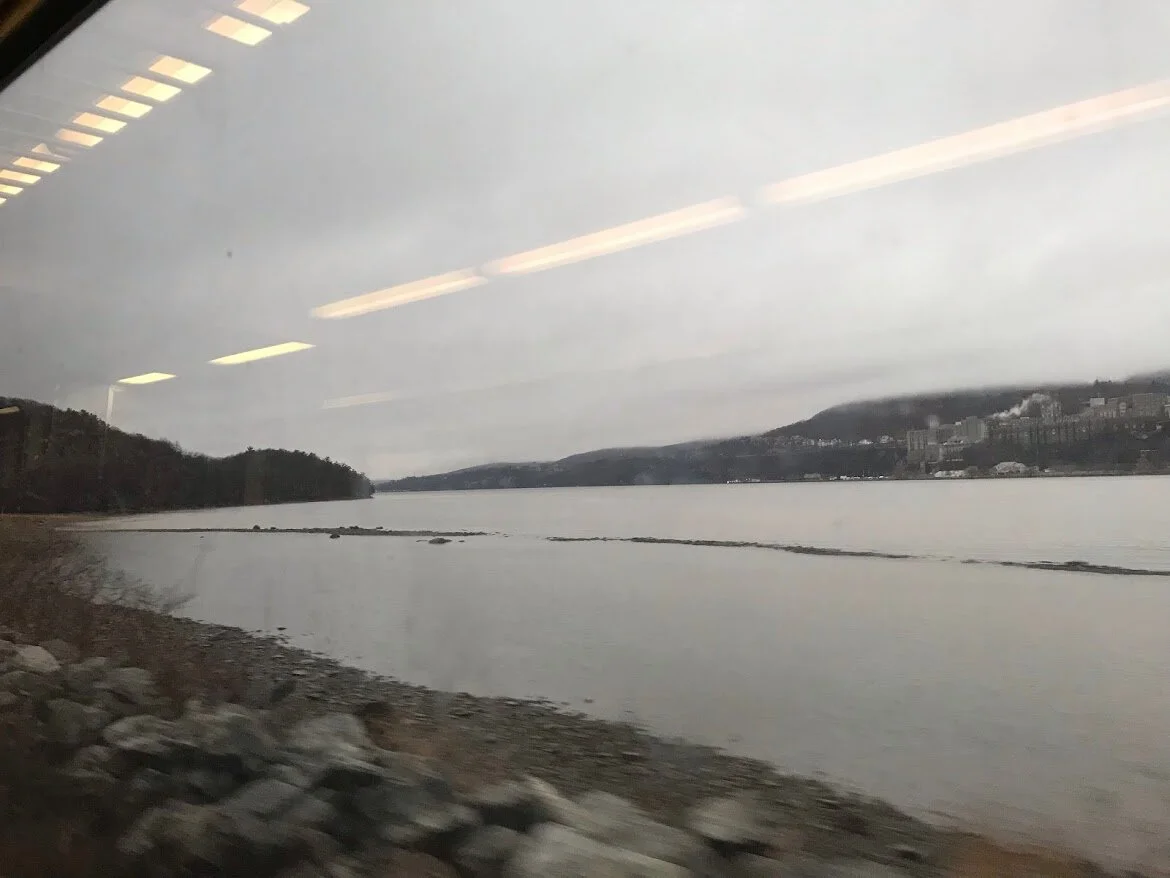

Sarah Heady is a poet and essayist interested in place, history, and the built environment. She is the author of Niagara Transnational, winner of the 2013 Michael Rubin Book Award, and the librettist of Halcyon, a new documentary-style opera about the death and life of a women’s college, currently in development with composer Joshua Groffman and producer Vital Opera. Her manuscript “Comfort,” a meditation on female solitude, agency, and relationship set on the prairies of the American West, was a finalist for the 2019 Ahsahta Press Sawtooth Poetry Prize and the 2017 National Poetry Series. Sarah is a co-editor of Drop Leaf Press, a women-run poetry collective that publishes visually and tactilely pleasing books from emerging writers.Although she lives in San Francisco, Sarah’s writing practice centers on New York State’s Hudson River Valley, where she was raised. In addition to the opera (which takes place in Millbrook, New York) and an essay collection circling around issues of landscape and class in the Hudson Valley, Sarah is currently working on “The Hudson Lines,” a book-length poem generated over four years of intermittent train rides on the Hudson Line of the Metro-North Railroad. Jenna Gersie spoke to Sarah about her poetic practice and place. Included in the interview are video, photographs, and poems by Sarah.How did you discover or create your writing practice on the Hudson Line of the Metro-North Railroad?

I grew up in Dutchess County, two hours north of New York City. It’s been sixteen years since I’ve lived at home—going to college in Ohio, living in Philadelphia and then small-town Tennessee, and finally moving to San Francisco almost eight years ago. I think it was this last move to the West Coast that started to bring out new levels of homesickness and wistfulness for my landscape of origin. And I was also in graduate school, reading project-based poetry books that were often generated through constraints or research or sustained, focused practices of some kind.

It was in this context that I devised my own poetic constraint: every time I returned home to the Hudson Valley from California and rode the Metro-North Railroad’s Hudson Line from Grand Central Terminal to the end of the line at Poughkeepsie, I wrote nonstop (by hand) for the entire ride. I did this every time I went to New York between December 2013 and December 2017, a period encompassing a total of perhaps thirty one-way trips. This writing practice was marked by time constraints: both the length of the train ride (between 93 and 124 minutes, depending on the train’s express or local status) and the seasonal timing of my visits “back East,” as we say in California. The resulting work documents this recursive series of journeys up and down the Hudson River, with the trip and its repetition serving as a mirror for the self.

near-vertical switch of granite:

this far north i am close to the cutcan see it in every line

fire is silent

except for its licking

the frozen slip[estrangement]

a field that’s still all snow

then railvoice:

how i wish

these tiny waves would be my lap

While the train ride itself may be a container for your writing practice, tell me about the place that the train travels through, and how you connect to it.

This particular rail journey, whose tracks run north from Manhattan and hug the eastern bank of the Hudson River for most of the line’s seventy-four miles, is world-famous for its natural beauty. Of course, it’s also deeply familiar to me (although one aim of the constraint was to challenge my own sense that I knew it so well). Prior to starting this project, I’d taken the same ride dozens of times, and its associated landscape is intrinsic to my notion of home. The Hudson River was the central geographic feature of my childhood, the primary reference point for all movement, and probably the thing that nurtured my place-sensibility.

I think of this quote from Freya Mathews: “A loved place holds us, even if it exists only in memory; it causes everything within it, including ourselves, to glow. A loved place is not encompassed by our love; we are encompassed, loved, breathed into life by it.” That’s how I feel when I board one of those Metro-North trains, with their unmistakable blue and red vinyl seats: totally alive, awake, tender, nostalgic, curious, grateful, openhearted—good conditions for writing, no?

(Speaking of good conditions, it was critical for me to nab the correct seat for this writing practice: always the westernmost side of the aisle, closest to the river, and ideally facing the same direction as the train’s motion, although I did experiment with facing backwards sometimes.)

The view out the window changes drastically over the course of the Hudson Line’s path: from the density of Harlem, the Bronx, and Southern Westchester County to the heart-stopping Hudson Highlands, where the Appalachian range intersects with the river at its deepest, most fjord-like point (the Hudson is actually a tidal estuary). This bucolic and serene journey is also punctuated by iconic institutions of war, destruction, and oppression like the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Sing-Sing Correctional Facility, the Indian Point nuclear plant, and Bannerman’s Castle (a former arsenal). As the train moves northward and New York City’s influence appears to wane—warehouses and apartments giving way to rolling hills and mountains—that influence is actually just transmuting as the built environment begins to reflect the immense wealth derived from City-based capitalistic pursuits. It also reflects the victories of the American environmental movement, which was born on the Hudson and has preserved enormous swathes of land from development.

So the journey is endlessly fascinating to me, obsessed as I am with human geography, architecture, urbanism, etcetera. And it’s also the story of my own northerly movement up the river: I was born in Manhattan and spent my babyhood in White Plains, my childhood in Beacon (before it was cool), and my teenage years in Rhinebeck.

How do movement and time play into your writing practice?

For me, this constraint enabled a contemplative practice of active attention, wakefulness, witness, reflection, deep seeing—and all these modes are in tension with the swift movement of a train. Deborah Tall writes, “From a speeding car . . . nature becomes little more than cinema, or a startling photo in the rearview mirror, receding. It is thrilling backdrop, but backdrop only, for the real action—the hurry through. It is scenery.” I of course agree with her that we must get out of the car at some point to truly know a place, but I also think you can fall in a certain kind of deep love with a landscape precisely because of this kind of mechanized travel.

Alongside the deep seeing of place, taking the same ride over and over again set a baseline for investigating and documenting my spiritual and emotional condition. The ride offered me space to reflect on change and constancy within myself, and each record of the journey became a palimpsest of landscape and life. The linearity of the train’s trajectory was sort of productively confused and cyclically layered with the other times I’d made the same journey and “seen the same things,” both within the frame of the project and before it. It’s thrilling and sometimes painful, the constant surprises that crop up with close looking and revise one’s understanding of a place and of oneself. I often think of these lines from Alice Notley’s The Descent of Alette:

“I thought” / “there was a place” “where everything was intact” “& this was that place”

This suggests nostalgia for a home-place as well as the larger issue of solastalgia, both for specific places impacted by ecological crisis and for the earth as a whole—like, is there such a thing as intactness anywhere right now? And I do conceive of this project as an ecopoetic one. Jonathan Skinner says that “ecopoetics is not [always] a matter of theme, but of how certain poetic methods model ecological processes like complexity, non-linearity, feedback loops, and recycling . . .” That is definitely part of the recursiveness of this practice for me—there was something about the returning, the recommitting, that felt like an ecological process, as well as a human kind of movement through grief.

What writing did you do on the train? How did place, and being on the train, influence that writing?

In writing under this constraint, the basic task I set for myself was to wakefully document the interpenetration of interiority with the ever-shifting external landscape seen through the train window. For me, the river functioned as a literal channel of communication between inner and outer worlds; I used the things I saw as prompts and as metaphors. I brought in my preexisting knowledge of places and creatures and landscapes, as well as my speculations. So the content was certainly dictated by my moment-to-moment experience of place. But because the constraint was to write nonstop, and to look inward as well as out the window, my mind (in its mind-ness) would definitely bring in “disconnected” things from far away or deep down, and that stuff made it into the freewrites. (Doesn’t mean I’m not editing it out now, though!)

Given the place-bound nature of the constraint, the work was sporadic, but also rigorous. I would often be running on no sleep while doing it, having gotten off a red-eye from San Francisco and transitioned (not quickly; there would be two hours of AirTrain/subway in between) onto a northbound train at Grand Central. It was almost like a “durational” practice, because (for me) it requires physical endurance to write by hand for that long, especially when I’m tired. And, actually, part of my winding the project down after four years was the fact that I was having a lot of pain in my hand and arm from writing like that (and more generally from computer use), and I decided it wasn’t worth it to hurt myself anymore. Since 2018, when I take that train ride, I might write a few small fragments, which are filling in some gaps as I’m editing the manuscript, but I don’t generate the volume of material I did in the thick of the project. I think a lot about how physical limitations factor into my writing practice now; for me the ends do not justify the means, so this project could not happen in the same way now as it did before my increased awareness of my body in the physical act of writing.

i am not saying the river is a being with something to tell. i am treating her as an endless depth, though we all know she has a bottom. of all the questions i want to ask this river, the most urgent is how to stay. but she’s the last one i should be asking.

How has “The Hudson Lines” evolved during the revision process? Did you do any of that revising on the train?

I have not yet attempted to revise on the train—great idea!

As the constraint (freewriting nonstop for up to two hours) might suggest, I’m a maximalist in the generative phase. My editing process, as with all my other projects, has been to cull down from a far-too-huge pile of material. I probably started with three hundred or so pages, and now it’s about one hundred and fifty, and it will become much shorter, I’m sure, both within individual poems and as a whole. I’m always aiming for concision. I guess I make a lot of work for myself by starting with so much material, but that’s my process.

The poems shifted in form over the four years; they started as dense prose blocks and became long, skinny, and lineated. They also became more philosophical and less narrative. And a number of the poems are epistolary. So in putting this manuscript together now, I’m thinking about organizing principles: form, voice, chronology, geography, directionality (northbound versus southbound). It still feels pretty early in the book-assembly process.

I also want to mention that some of “The Hudson Lines” have been set to music! Before we started writing our opera, Halcyon, Josh Groffman composed this piece for soprano, baritone, and piano that uses five of the early prose poems from the series. Josh is a place-centric artist, and he also grew up near Poughkeepsie, so it’s really special to collaborate with him on Hudson Valley projects.

the region

on its kneesthe train car a wheeled

conservatory, full of

chambered sunlight and breathing:two metal streams

paralleling myalways-water

Why do you think a sense of place is important for writing practice?

In my experience, the active cultivation of a soul and body connection to place clarifies my purpose, brings my life into relief, contextualizes my humanity and my relationships, and adds vibrancy to my settledness. All of these things make me a better writer.

It’s also okay to be passive sometimes. The last time I took the Hudson Line from Grand Central to Poughkeepsie, I had the choice of running to make a train on which I knew I would not get a window seat, or waiting half an hour for the next one and landing the ideal “Hudson Lines” seating scenario. And I ran. I just wanted to get home, I wanted to eat dinner, I wanted to see my parents. I’m not saying I didn’t resent the people with window seats who played on their phones or read trashy romance novels all the way to Poughkeepsie without looking out the window once; in fact, in a panicky moment, I almost asked one of them to switch seats with me “because I was visiting from California,” but I decided that was nuts. And I reminded myself that something I’d been working out in the project was healing my own pattern of scarcity thinking: the fear of missing out on the view.

Still, as I hear some authoritative voice telling me to calm down, “The river’s not going anywhere,” I know that’s not true—not only for the fact that the river is literally going somewhere, is always different, but also because we can no longer count on any earth-feature to remain constant. And living with that truth is a personal spiritual practice, and a collective one, and also a creative one.

Jenna Gersie

Jenna Gersie is a PhD student in the English department at University of Colorado Boulder. She is managing editor of The Hopper.