Nonfiction

MAY 2019Swallowtail Summer:

Generations of Ecology in the Art and Science of Maria Sibylla Merian

by KAYANN SHORT

[A] caterpillar doesn’t end at its last segment, but stretches to include the flower it eats, the season it molts, the leaves it webs into its cocoon, the parasitoids that lay eggs there, the moth it becomes.

—Kim Todd, Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis

The first swallowtails appear in late May. A shadow over my shoulder, a glimpse of damsel in yellow and black, these flutterings soon occur often enough for me to realize I am seeing more swallowtail butterflies than I have ever seen before. In June, I start asking others whether they have noticed the swallowtails too. Upon consideration, many folks agree more of the butterflies seem to be around than usual. What accounts for their increase? A wet, cooler spring? More vegetation, leading to better conditions for their pupae? A heavier crop of caterpillars from the eggs laid the autumn before?

A week before my grandson’s fourth birthday in early July, we make plans for him to stay overnight at our farm for the first time without his parents. For days before he arrives, we talk about the things we will do: collect eggs from the chickens, pick vegetables for dinner, pet the goat, jump on the trampoline, and make pancakes for breakfast. Our farm, Stonebridge, is a CSA, or community-supported agricultural farm, on Colorado’s Front Range. We provide weekly produce to subscribers rather than sell to stores or at farmer’s markets in order to create a community that supports land preservation for organic, healthy food production. As soon as my grandson gets to the farm, he jumps out of the car to give me a big hug and I tell him we need to check the barn to be sure we have enough vegetables for our members to pick up that day.

As we walk hand in hand along the stone path, two swallowtails appear in front of us. I’ve seen swallowtail pairs on the farm before, floating elegantly like ladies in striped evening gowns on their way to the ball. But this pair isn’t flying, at least not in a straight line. Instead, they’re circling swiftly around and around each other as if caught in a whirlwind from which they can’t escape. Even while spiraling, they remain equidistant, twirling within an invisible tube, their pairs of wings seemingly connected like two sides of a propeller revolving around some center we cannot see. I realize they must be mating, but I’ve never been close enough to a pair of butterflies to feel the pull of air as they spin in a lepidopterous pas de deux.

As my grandson and I watch this cyclone of tandem flying and whirling, the swallowtails spin toward the barn. We follow, curious to see whether they’ll fly right through the open door. But they stop short of entering, instead rising straight up in a gyre above our heads and, still circling, spiral downwards like water through a drain, skimming the stones on which we stand. All we can do is remain motionless, waiting to see if they’ll land at our feet. Then, just before alighting, the swallowtails ascend one last time in their airy column before their coupled force is broken and their linked flight unbound. Wings beating gracefully in solo rhythm, they fly their separate ways over the ditch and are soon gone.

My grandson and I look at each other in amazement. “Butterflies!” we cry, as if that one word captures the dance witnessed by our eyes alone. Then my grandson laughs and pulls my hand. “Come on,” he says, and we’re off on another adventure, a whirlwind of child and grandmother as free as butterflies in the summer sun.

Summer Birds

I first became aware of the seventeenth-century naturalist and artist Maria Sibylla Merian in a children’s picture book I ordered for my grandson’s fourth birthday: Summer Birds by Margarita Engle with illustrations by Julie Paschkis. Narrated in the youthful Merian’s voice, Summer Birds follows the trajectory of her childhood as she gathers and studies butterflies and moths, known then as “summer birds” since they only appeared in warm seasons.

My grandson loves drawing animals, so I bought Summer Birds because I wanted him to see how art and science combined could both teach and delight through observation, illustration, and, most of all, wonder. While the book’s pictures are colorful and imaginative, they do not try to rival the precision of Merian’s own art. Rather, they show her doing things that most girls of her time didn’t do, like raising caterpillars and drawing bugs.

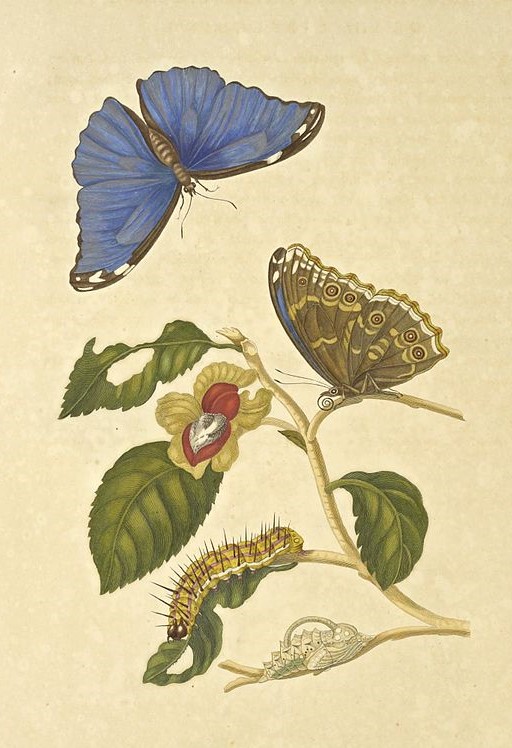

The confluence of many aspects of our current world—the rise of science, international trade, global information networks, and women’s education—dates to the late seventeenth-century and early eighteenth-century world in which Merian lived. To today’s viewer, Merian’s art is astounding for its beauty, with each plant and insect engraved and painted so close to the colors and poses of nature they come to life on the page. Viewers must look with an eye to history, however, to see the scientific innovation of Merian’s work, for her portraits of insects in simultaneous stages of their life cycles—egg, larvae, pupae, and butterfly—within their actual habitats have become the standard depiction of the natural world today. Tracing the life and legacy of this remarkable artist, scientist, entrepreneur, and publisher reveals how earlier views of nature, knowledge, and gender are relevant to our own ecological debates, for Merian created not only a new way to draw, but a new way to see, the world and all its wonders.

Maria Sibylla Merian was born April 2, 1647, in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Merian’s father was the Swiss engraver and publisher Matthäus Merian the Elder, whose sons from his first marriage worked in the family print shop. Growing up, Maria Sibylla was certainly familiar with her great-grandfather Theodor de Bry’s influential book of floral still lifes, Florilegium Novum. Little is known about Merian’s mother, Johanna Sibylla née Heim, but an early Dutch biographer, Arnold Houbraken, linked Merian’s fascination with insects with her mother’s unusual obsession with collecting bugs during Johanna’s pregnancy.[1] Whether or not this is true, it highlights the unconventional nature of interests Merian would follow her entire life.

After Merian’s father died in 1650, her mother married artist and dealer Jacob Marrell, who encouraged the young Maria Sibylla to paint. Marrell’s paintings often incorporated insects, reptiles, and other small creatures as objects of interest and perspective into his floral still lifes, an influence that can be seen in Merian’s early depictions of flowers. Her engraving skills were probably learned from working with her stepbrothers in the family shop. Growing up in an artistic household in which male members mentored female talent was unusual. Merian is all the more remarkable for developing her skills in a society in which women could not be members of painting guilds or pursue university studies.

Through her stepfather, the young Merian was exposed to the work of other artists of the day, sometimes copying their paintings as a way of learning, an accepted practice at that time. One influence was undoubtedly the artist Johannes Goedaert from Middelburg, who was not only a painter, but also published Metamorphosis naturalis, a work portraying the metamorphosis of caterpillars into pupae and then into butterflies. While Goedaert was one of the first to propose metamorphosis as the transformational life stages of invertebrates, he was still a believer in the Aristotelian theory of spontaneous generation, the idea that living organisms could arise spontaneously from non-living substances such as soil, manure, or dead flesh rather than from fertile material such as eggs or seeds.

In her early teens, Merian began to investigate the metamorphosis of silkworms, which at the time were being developed in Germany for their commercial potential in establishing a silk trade. Following the superstitions of her day, Merian’s observation of metamorphosis over spontaneous generation and her interest in insects—or “bloodless creatures,” as they were called—might have made her vulnerable to charges of witchcraft for meddling in matters beyond the human realm. No record suggests that Merian herself was threatened with these allegations, but she was likely aware that her unusual hobbies might be subject to accusation. Perhaps her membership in an important Frankfurt family protected her from such charges.

Merian’s introduction to Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam provides an early glimpse into her youthful entomological research in observing the life cycles of living insects, rather than merely painting them from preserved specimens, as was the practice of the time:

“From my youth onwards I have been concerned with the study of insects, in which I began with silk-worms in my native city, Frankfurt am Main; then I observed the far more beautiful butterflies and moths that developed from caterpillars other than silk-worms, which led me to collect all the caterpillars I could find in order to study their metamorphosis. I therefore withdrew from society and devoted myself to these investigations; at the same time I wished to become proficient in the skill of painting in order to paint and describe them from life.”[2]

This account offers insight into a principle that Merian followed throughout her life: working with live creatures was more valuable artistically and scientifically than working from dead ones. Even in her later years, as she wrote to English apothecary James Petiver in 1705, she “was not looking for any more creatures, but only at the formation, propagation, and metamorphosis of creatures, how one emerges from the other, the nature of their diet. . . .”[3] One might even argue that this ideal provided a foundation for many of the decisions in Merian’s life. When she could choose the conditions and subjects of her art and research, she chose living creatures in natural environments.

In 1665, Merian married her stepfather’s apprentice, Andreas Graff. She continued to add Merian to her name after marriage, which allowed her to draw on her father’s artistic reputation, but may have been claiming her own identity independent of marriage, as well. The couple’s first daughter, Johanna Helena, was born in 1668; in 1670, the Graffs moved to Nuremberg, Germany, where Andreas’s family was located. Here Merian worked on the engravings based on watercolors for her Book of Flowers Primus in 1675 and Alter in 1677, each with twelve plates printed as individual pages and sold as fasciculus, unbound sets.

Simultaneous with the 1680 publication of Tertius, the third in the series, was the re-issuing of the first two with the third, now bound in a book called New Book of Flowers. According to its title page, this book was “diligently produced for the Pleasure, Use and Benefit of All Art-Minded Collectors.”[4] As patterns for embroidery and needlework, which Merian taught to young women of the noble classes, these books were seemingly intended as commercial, as well as artistic, ventures. Although the watercolors focused on flowers, often Merian included insects—a butterfly nosing a bloom, a spider weaving a pansy web, a beetle scuttling under a bouquet—revealing her continuing interest in entomology, a term that had not yet been coined.

Joachim von Sandrart[5], a contemporary of her father’s, complemented Merian’s portrayal of insects and metamorphosis in his history of German art and architecture. He also remarked on Merian’s talent in painting on silk and other fabrics with washable pigments, none of which survive today. It is important to note that Merian worked in watercolor because women in Germany at that time were not allowed by the policies of the craft guilds to paint in oil, a restriction that gave male artists a commercial advantage in commissioned paintings such as portraiture and landscape. The publication of Merian’s flower books shows not only how she worked, but excelled, despite the limitations put upon her.

New Book of Flowers evidences the nascent tension Merian acknowledged between art and science. In a poem by Merian at the beginning of the book, she acknowledges the artist’s struggle to provide “equal line and strike” in the object she attempts to portray. This poem is notable for giving voice to the mission Merian gave herself in life, faithfully reproducing through art what she observed in life: “Thus must art and nature always with one another contend / Until each has conquered to the end / . . . Thus must art and nature kiss and embrace as twain. . . .”[6] This dual mission can be seen as Merian’s art developed alongside her scientific knowledge, with insects becoming more than embellishments by moving into the foreground of her paintings, while plants became habitat rather than merely pretty flowers to imitate through the feminine arts.

Merian’s ongoing interest in raising, observing, and drawing insects came to the forefront in her next book, The Wonderful Transformation of Caterpillars and Their Singular Plant Nourishment, as she turned from flowers to the subject of her ongoing research into metamorphosis. The first volume of this work, containing fifty engraved and etched plates with captions in German, appeared in 1679, the same year as the birth of Merian’s second daughter, Dorothea Maria Henriette. This Caterpillar Book, whose title page proclaims the book’s wide use for “natural scientists / painters / and lovers of gardens,”[7] was the first published work showcasing original naturalist observation with exquisite artwork. The book was prefaced with a poem by her friend Christoph Arnold placing Merian in the ranks of famous naturalists while calling attention to her gender: “It is remarkable / that women also venture to write for you / deliberately / what has given flocks of scholars so much to do . . . we shall hold the same tests; and show what can be done / by his daughter’s diligence / the worthy Merian!”[8]

The second volume of The Wonderful Transformation of Caterpillars was published in 1683 in Frankfurt, where Merian had returned after the death of her stepfather to help her mother. Like the first volume, the second included fifty plates “again engraved and published by Maria Sibylla Gräffin, daughter of the late Matthaeus Merian the elder.” In these volumes, we once more see how art and science in Merian’s time were not yet considered two separate fields of study, for in those days before photographs, art provided the visual methods for recording scientific research. Although scholars disagree whether Merian’s reference to her “entirely new invention”[9] refers to her depiction of life-cycles, a magnifying glass, or a microscope, it is clear that with her Caterpillar books, Merian’s artistic and scientific skills came together to offer new information in new ways.

In 1685, Merian separated from her husband and moved with her mother and two daughters to a religious community of Lapadists in the Friesland province of the Netherlands, where Merian studied caterpillars for a third edition of her caterpillar book and also worked on the study book she had kept for many years. When the community suffered economic misfortunes, Merian—now a single mother—needed to make a living, so in 1691, following the death of her mother, Merian and her daughters moved to Amsterdam, where she could establish her own business selling specimens, prints, and pigments. Her eldest daughter, Johanna, married merchant Jacob Hendrik Herolt. Amsterdam at that time was a large and important center of international commerce and travel, offering Merian access to naturalist resources through her acquaintance with collectors and gardeners.

In 1699, Merian, now fifty-two, and her youngest daughter Dorothea embarked for Surinam, a voyage now considered the first self-funded, non-sponsored voyage by a naturalist, made even more remarkable for being undertaken by two women, unaccompanied by men. An advertisement in a Dutch newspaper reveals that the money for this expedition was raised from the sale of Merian’s art and specimens.

In Surinam, the women studied and recorded insects in their natural environments, sometimes traveling to remote jungles with local guides to find species unusual and interesting to European collectors and scientists. These guides were likely slaves of the large plantations visited by Merian and Dorothea. As she had in Germany, Merian collected and raised caterpillars, keeping detailed notes about her research, including information learned from her guides. For example, Merian notes that peacock flower berries are used by indigenous women to induce abortion so that their children will not be enslaved, a fact that a male researcher may never have learned or noted.[10]

Merian and Dorothea planned to remain in Surinam for five years, but returned after two due to Merian’s ill health. Her illness may have been malaria, possibly the source of continuing health problems. Mother and daughter left Surinam in June 1701, returning to Amsterdam in September. Ship records show an unnamed native woman returned with them, but nothing further is known about her life.[11] Given Merian’s health, this woman may have been hired to help with the return voyage, but she probably also provided valuable assistance in compiling the information for Merian’s Surinam book. Unfortunately, her story has been lost to the colonialist erasures of her time.

Upon her return, Merian began work on a new book, financed through pre-paid subscriptions, featuring the creatures and plants observed, painted, and recorded on her trip. Dorothea Maria married Philipp Hendrikes, who contributed to the family income by bringing back specimens of insects and animals for sale from his travels as ship surgeon on voyages to the East Indies. To earn money while working on the Surinam book with her daughters, Merian became an illustrator for a book based on the collection of German naturalist Georg Everhard Rumph, The Ambonese Curiosity Cabinet, which was published in Amsterdam in 1705. Although Merian did not sign her name to these illustrations of shells, rocks, fossils, and crustaceans, her skills as a miniaturist are evident in the originals later found among her collected works.

In 1705, four years after her return from Surinam, Merian published the work considered her magnum opus, Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam in Dutch and Latin. In Merian’s introduction, she once again emphasized her life-long commitment to portraying “beautiful creatures” in their natural habitat, rather than from preserved specimens: “In every collection I found these and countless other insects, but also in each, the insects’ origin and propagation were absent, that is, how they transformed from caterpillars into pupae and so forth.”[12] This book was groundbreaking for its meticulous depictions of living insects in their natural habitat painted in New World colors, and for introducing the folio book size with pages large enough to portray the interaction of organisms with each other and their environment. Metamorphosis revealed curious creatures and exotic plants never seen before in Europe. For example, Musa paradisiaca, her portrait of an arching banana plant with its lush red petals and sensual yellow curves, upon which crawls and flies the intriguing io moth in all its intricate stages, introduced this fruit to viewers more than one hundred years before it would be imported to Europe.

To produce this book required funding a long voyage to a foreign country, crawling through jungles, acclimating to severe heat, compromising her health, and disrupting her life back in Amsterdam. Few artists or scientists of her time made such journeys or undertook such a project as Merian’s, but her driving force to observe and record creatures in their own environments would birth the new idea of what we now call “ecology” to the forefront of naturalist study.

Drawing Creatures

At four, my grandson announces he knows how to draw red pandas. “They have a long narrow body.” He draws a long oval. “They have long arms, too,” he tells me as he draws. Then he adds a round head, small ears, and a big tail. “I almost forgot. The tails have rings.”

“That’s a red panda?” Obviously, I’m not familiar with red pandas; this one looks very different from the roly-poly pandas I imagine.

“Yes, I’ll draw another one in a tree. They have sharp claws for sticking to the tree.” He draws a second, smaller red panda and a tree to go with it. I note that he drew the red panda in its natural habitat, a new step in his depictions of animals.

That night as we eat dinner, my grandson is unusually quiet. He seems to be weighing something in his mind. Finally, he turns to his mother. “Do you think I can draw a hammerhead shark?”

“You can definitely draw a hammerhead shark.”

“I would use squares for the sides of its head,” he decides. I can see his sense of artistry emerging as he turns ideas over in his mind, considering the image and how he might re-create it on paper, including the geometric shapes he would need.

I have been watching my grandson draw since he was two, turning what most people would call scribbles into animals. He had an Etch-a-Sketch-like tablet he called his “iPad” on which I’d draw animals for him. My art skills are limited, but I could turn out something rudimentary enough to be recognizable.

After I taught him to draw circles, my grandson started combining them with lines to make heads, bodies, legs, and tails. I showed him how legs could appear on different sides of an animal’s body and he figured out that distance changes how objects appear larger when they’re nearer and smaller when they’re farther away. When he would get frustrated with his picture because it didn’t look the way he thought it should, I would remind him that every artist has to practice—a new word for him that meant “do over and over”—to learn better ways to draw.

By three, my grandson was figuring out how to put shapes together on his own to make all kinds of animals. One day when he is drawing a bear, I tell him he is a good artist. “I’m not an artist,” he shakes his head.

“Why do you say that?” I ask.

“Because I want to work with animals.” He has told me this career plan before; other times he says he wants to protect animals when he grows up. When he’s four, careers like “biologist” and “illustrator” will enter his vocabulary, but, for now, it’s the taking care of part that he understands.

“Sometimes part of working with animals is drawing them,” I suggest. “Like for a book or to show their picture to someone. Sometimes people who work with animals are artists too.”

That idea seems to fit a three-year-old’s sense of practicality. “Okay,” he says, and keeps drawing.

In 1713 and 1714 new editions of Merian’s Caterpillar books I and II appeared in Dutch. These editions added new insects to previous engravings and deleted all references to the spontaneous generation of flies from excrement that Merian had included so many years ago. Her decades of observations had proven the fallibility of this outdated theory and she was ready to assert her first-hand view of metamorphosis.

In 1714, Merian suffered a stroke and was paralyzed; her daughters continued to work on the third caterpillar book. With Johanna’s skill in plant portraiture and Dorothea’s in animals and engraving, they were essential collaborators to Merian’s last original book. As Ella Reitsma points out in Maria Sibylla Merian and Daughters, while the term “cottage industry” casts images of women sewing, weaving, or knitting to make a meager living at home, in Merian’s case, home was the center of an international trade in not only important original art, but exotic specimens collected from the Surinam venture and other travels undertaken by Dorothea, Johanna, and their husbands. Johanna, in particular, seems to have gained her own reputation as a painter, although never as celebrated as her mother, while Dorothea’s skills continued to provide a living for her and her second husband, painter Georg Gesell, reinforced by Merian’s name and influence.

On January 13, 1717, Maria Sibylla Merian died and four days later was buried in a middle-class Amsterdam grave. Less than two weeks before her death, Robert Areskine, an agent for Peter the Great of Russia, bought two large portfolios of paintings on vellum for the Tsar, as well as Merian’s study book for himself, which was bequeathed to the Tsar upon Areskine’s death in 1718. Here Merian had compiled sketches and small paintings of her research since she was a young woman, along with commentary and indication of how they were used in her published works, a valuable resource for scholars today.

Following Merian’s death, her daughters finally published the new third section of the Caterpillar book alongside the first two sections in a 1717 Dutch edition including fifty new plates with accompanying text. In the revised introduction, Merian wrote of the “miraculous being and beauty of such tiny little Animals that no Painter with Brush and Paint can reach it.”[13] This artistic assessment differs dramatically from the poem in Merian’s New Book of Flowers in which she states “[t]hus must art and nature always with one another contend, until each has conquered to the end.” If this statement was an acknowledgment that in the struggle between art and nature, nature won out, had Merian been humbled by age? Or was the statement required by religious sentiment, as might have been expected for an artist of her station? Certainly, if anyone has come close to capturing “tiny little Animals” with “Brush and Paint,” it is Maria Sibylla Merian.

In 1718, Johannes Oosterwyck reissued the full Caterpillar book in Latin. According to public records, Oosterwyck had acquired prints and plates for this book from Dorothea before her departure with her husband for St. Petersburg in 1718 to train pupils and organize collections for Peter the Great. After the Tsar’s death, they worked for the National Academy of Science, the repository for Merian’s works. Other drawings purchased in Merian’s lifetime by London doctors found their way to the British Museum and Windsor Castle under George III. For a tradesperson of her time, Merian’s influence at her death had already reached extraordinary international scope.

Lepidoptera

I love butterflies, but I’m no lepidopterist. After I notice the unusual number of swallowtail sightings on our farm, I decide I better learn more about this beautiful order of insects. I discover that butterflies are the second largest order of insects, next to beetles, and that swallowtails are in the family Papilionidae that includes, at last count, 552 species. Next I buy a guide to butterflies in Colorado; here I find four species of yellow-and-black swallowtails—but which had I been seeing that summer? Then I remember a dead swallowtail I’d preserved a few summers before and photographs of another dead swallowtail I found clinging to a rosebush. I check both of these artifacts and find they are quite similar, both with blue and orange markings on their lower wings. The preserved butterfly has the distinctive double tail of Pterourus multicaudatus, the two-tailed swallowtail, while the photograph reveals the dual orange spots of Pterourus rutulus, the western tiger swallowtail. But I’m still not sure which—if not both—I am seeing on our farm that summer.

I also learn a little bit about this Papilionidae’s habitat and metamorphosis. Host plants for swallowtail larva—or caterpillars, as they are generally known—are cottonwood, aspen, willow, wild cherry, and ash trees; all except cherry are found along the irrigation ditches at our farm. I look up pictures of swallowtail caterpillars, green with yellow-and-black stripes. They look familiar; I suddenly realize I am guilty of disposing of some of these creatures because I thought they might harm crops. Now I know to let them be or move them somewhere else. I also discover something I should have known before: in the pupa stage, a butterfly forms a chrysalis, while moths spin cocoons. But maybe that ignorance is not surprising in someone who once thought sphinx moths hovering with quickly beating wings to drink nectar from flowers were hummingbirds. Our natural world is so wildly complex, no wonder I have so much to learn. The most important lesson Maria Sibylla Merian has taught me is to pay attention.

Following her death, the importance of Merian’s work was acknowledged by eighteenth-century naturalists in Germany, France, and England, but by the nineteenth century, critics began to question the accuracy of Merian’s work, in part because of the poor quality of reproductions and the omission of Merian’s textual descriptions. In unpainted copies of the book, others would re-color the illustrations using inaccurate hues, a problem for which Merian was later criticized. Similarly, later editions of her books included new plates drawn by other artists but falsely attributed to her; and in other cases, books lifted her insects and animals from their life cycles and habitats. These alterations of her originals cast aspersions on her reputation as an artist and a scientist.

Of particular concern to some later scientists was Plate 18 of Insects of Surinam, which showed a hummingbird attacked by a tarantula. Although these naturalists had never traveled to Surinam themselves, they questioned the possibility of what they termed “bird-eating spiders.” Even after other nineteenth-century biologists—and suffragists—defended and proved her portrayal[14], the controversy continued, for how could an uneducated woman, lacking university training in the sciences, possibly get it right? It wasn’t until her work became available in the twentieth century that biologists studying her pictures noted how remarkably few her errors are in both depiction and description, especially given the wide scope of her research and the fact that she was working before scientific nomenclature or taxonomy were definitively established.

For Merian, of course, was conducting research and documenting animals and plants before Linneaus created his classification system. Her concern was not with categories and names, but with accurate depictions that could be used for such. The value of her work is seen in the fact that Linneaus himself used her engravings to identify as many as one hundred different species. Her name even appears alongside his and other early naturalists when a new library wing was built for the Amsterdam zoological museum in 1872.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, Merian’s work began to see the light of day—literally, since, as watercolor, much of her work had been kept away from damaging light in the archives of collections in Russia, Amsterdam, Germany, and England. The benefit of this treatment was that her paintings were still vibrant, their magnificent hues still vivid. Perhaps, like a butterfly pupa emerging from a chrysalis, Merian’s art had been waiting for the right moment to emerge, for now her work can be appreciated through new ecological and feminist frameworks.

Beginning with a 1967 retrospective exhibit in Nuremberg, Merian began to assume her rightful place in the world of art. A 1974 edition of the Leningrad watercolors allowed new audiences of scholars and readers to view Merian’s work. In 1976 her study book was published as Butterflies, Beetles and Other Insects: the Leningrad Book of Notes and Studies, including unbound facsimiles of the small drawings and paintings she compiled over decades as models for her engravings and watercolors. Major exhibits of Merian’s engravings and paintings followed in 1981 in New York and in 1997 at her birthplace, Frankfurt am Main.

As the art world rediscovered Merian, what reception did the scientific community offer to her reemergence? In “Maria Sibylla Merian, the First Ecologist?,” scholar Kay Etheridge suggests that Merian has received more attention for her visual images than for her naturalist observations, leading to a neglect of Merian’s empirical contributions. Etheridge notes that Merian’s text was meant to augment and clarify her images and that Merian herself often pointed out in the accompanying text her inclusion of inconsistent or nonstandard details and the reasons behind them, details often overlooked by critics, in part because her books have not been readily or fully translated.

By establishing the influence of Merian’s work on other lepidopterists, entomologists, scientists, and natural historians, Etheridge notes the many innovations made by Merian, who was not only the first published woman naturalist, but self-published, at that. According to Etheridge and other scholars, Merian was not the first to portray the life cycles of insects, but she was the first to include male and female of a species, reproductive details like eggs and semen, multiple wing positions and colorations, and details only noticeable from living creatures such as movement, formation, and feeding habits, for how else to draw a butterfly’s proboscis than to watch it eat? Even more groundbreaking, Merian was the first to show creatures engaged in their natural habitat and with each other. Merian was the first naturalist to pair insects with their feeding preferences and to portray the struggle of interspecies survival, some of the foundational aspects of the modern concept of ecology.

Merian’s mission was to capture the dynamic world of insects and plants on the static page by filling the blank space with life. For her, art was the vehicle for documenting living beings in their environment, but with a twist: in nature, a complete metamorphosis could never occur in a single setting with all stages in a single scene, yet Merian’s paintings depict creatures developing in one place and time, a kind of time-lapse representation of one habitat in one cyclical moment. As Reitsma notes regarding Merian’s combining of art and science in one image, “The beautifully balanced composition conjures up a seeming realism, for the successive stages in the development of an insect can never be found together. Tricks have been played with time and place.”[15] In this “seeming realism,” we glimpse a moment before science was separated from art, for collapsing an entire life cycle into one scene is a standard method of scientific illustration today.

Butterfly Pavilion

A month after my grandson’s overnight stay at the farm, I suggest a trip to the butterfly pavilion near where he lives. In the butterfly house, an immense, humid room with a glass ceiling, we wander along paths and over bridges looking for colorful butterflies in the midst of the thick, tropical foliage. My grandson holds out his hand patiently for a butterfly to land, but they fly on by. We pretend we are explorers looking for butterflies in the jungle and call out their colors as they float by. I hope to capture an image of the elusive blue butterfly, but it’s as hard to capture a butterfly in flight as it is a four-year-old child.

In an exhibit near the door of the butterfly room, I read that the blue butterfly is called a common blue morpho. The dorsal, or top side, of the wings are blue as we could see in their flight, but the ventral, or under side—the side seen when a butterfly is at rest with its wings upright and closed—is brown with eye-like circles, much like the eye-spots of the owl butterfly, also in residence at the pavilion. No wonder I can’t find a blue butterfly resting on a plant—the blue only shows in flight. Yet Merian painted blue morphos in different positions on the page so both sides of their wings would show. I try to imagine discovering creatures like these in a jungle and documenting them for an audience hungry for knowledge of new species—and new collecting trends.

A couple weeks later, my grandson points out a butterfly with bright blue wings in the sticker book I bring him. “That’s like your favorite at the butterfly pavilion,” he says, referring to the blue morpho I failed to capture with my camera.

“What do you like about butterflies?” I ask him.

“They’re beautiful,” he says. He laughs when I tell him his mother called butterflies “flutterbys” when she was his age.

We look up the pavilion’s website to compare my photographs of our visit with the butterflies found in the exhibit. One of the moths and another variety of swallowtail match mine. Then I notice an educational display in a photo I took in the play area while my grandson climbed a rope spiderweb. The panel illustrates the life cycle of a dragonfly with other creatures and plants in a pond, a picture modeled on Merian’s ecological engravings of insects in their natural habitats, proof that three centuries later, Merian’s work continues to influence our understanding of the natural world.

Although Merian’s empirical contributions may still be overlooked, the biographical aspects of her life as a natural historian are being recognized, especially for the ways she challenged gender roles of her time. Merian is now included in books devoted to important scientists and scientific discoveries, books whose titles include words like “great,” pioneering,” “trailblazer,” “headstrong,” and “fearless,” and her story appears in compiled biographies of “great naturalists.”

New editions of Merian’s work continue to be published, bringing the books she once engraved, painted, and published herself to an international audience of new readers. In 2016, a new facsimile of Merian’s 1705 Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam reproduced the original sixty illustrations in full size with new commentary. Here Merian’s research is given its due: all of the insects, animals, and plants are verified by the Naturalist Biodiversity Center.

Considering Merian’s diligent trade with collectors during her lifetime, she would surely have been pleased to have her books and prints find their way into similar hands three hundred years later. Merian’s original publications have also achieved great financial value, obtaining six-figure prices she no doubt would have found amazing. Were she alive today, however, Merian would have also undoubtedly been gratified to witness the public appreciation of her work. For example, the National Museum of Women in the Arts contains a permanent collection of biographical information; many outstanding websites are dedicated to her life and work; her images appear on stamps in many countries; Google “doodled” her 366th birthday; and in one YouTube video, caterpillars and butterflies crawl and fly right off the pages of her books!

Yet perhaps no recent honor would mean more to Merian than this: In 1902, a subspecies of the split-banded owlet butterfly that Merian hatched from a caterpillar she found on coffee senna leaves—a butterfly first shown on Plate 32 of Merian’s Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam—was given the scientific name Opsiphanes cassina merianae after Maria Sibylla Merian.[16] Although Merian herself was not concerned with the taxonomic classification of insects, this recognition by her peers—some two hundred years later—would surely have gratified her sense of justice. Just as the poem that prefaced her Caterpillar book predicted, Merian has taken her rightful place within the great names of scientific discovery.

Just as Merian looked past the last segment of her caterpillars to understand the ecosystem in which they lived, researchers today are connecting the taxonomic, ecological, artistic, and historical aspects of her pioneering work. For example, the Maria Sibylla Merian Society was founded to sponsor international conferences and symposiums on Merian research, while the wonderful exhibit “Second Life” by artist Joos van de Plas reinterprets Merian’s works in imaginative paintings, drawings, videos, and three-dimensional installations bringing her images to new life. Exhibits like this return to a time before art and science were divided, a time before those categories were affixed into discrete spheres of knowledge and expertise, a time in which an unschooled, middle-class woman working at the nexus of both could achieve unprecedented fame.

Metamorphosis

As an environmentalist and a grandmother, I want to encourage my grandson’s interest in animals, so I bring him a National Geographic magazine with a special feature called the Photo Ark that shows endangered species now living in captivity. Inside the cover is a camera ad featuring the Ili pika, a small, teddy-bear-faced, grass-eating mammal once believed extinct but now making a comeback in China. I show this to my grandson because I think Ili pikas are the cutest animals on the planet and I want him to understand that humans affect what happens to animals. My grandson already knows what “extinct” means and it makes him sad, but I explain that Ili pikas are returning because people are protecting them. Then we look at the animals in the Photo Ark. Several of the descriptions mention how near extinction an animal is, including the northern white rhinoceros, with only three now living in captivity. For each of these animals, my grandson assures me, “I think they’re coming back.”

If “metamorphosis,” most simply put, means transformation from one form to another, the process seems the perfect metaphor for Maria Sibylla Merian’s career. As a seventeenth-century illustrator and naturalist, she honed her skills and knowledge in ways that have transformed both art and science. Essential to understanding Merian’s remarkable accomplishment is to grasp that her innovations in art were also innovations in science; her creativity came from the synthesis of the two. For Merian, painting and drawing were research, as was the raising of caterpillars, the mixing of pigments, and the trading of specimens. Perhaps if Merian had been a man, she would have had to choose more firmly between art and science. Fortunately—and she did seem to enjoy a good dose of fortune for a woman of her time—she chose both.

“Metamorphosis” may also be the perfect metaphor for Merian’s unconventional life. After all, she dedicated herself to studying and capturing the miracle of transformation in small creatures. Could this fascination with metamorphosis have allowed her to weather so many changes in her own life as well?

If a caterpillar doesn’t end at its last segment, neither must the ecologist who seeks to understand it. To see, observe, study, portray, and record it all was Merian’s mission. As Merian noted in the epilogue to her first caterpillar book, her descriptions of what were “for some people perhaps contemptible things”[17] were accomplished for God’s grace to “shine forth more brightly and more splendidly among us earthly-minded people.” And she adds: “As I would otherwise never have begun this tedious little work, much less allowed myself to be persuaded to print it, especially since people consider such as an inappropriate ambition for women (who must do this aside from their household worries).”[18]

But even while she challenged rigid gender expectations of her time, Merian could not have predicted the political and economic forces driving the ecosystem devastation now threatening the very subjects she studied. Thus Merian’s life stands at one end of a global ecological movement and the world today stands at another. While debates about protecting the environment have become all the more pressing within today’s reactionary and anti-progressive politics, becoming more “earthly-minded” in an ecological sense becomes ever more urgent. My hope is that further attention to her vision provides one more inspiration for preventing further destruction of terrestrial biodiversity—life on planet Earth as we know it.

Autumn Butterflies

In late August, I catch a glimpse of the last swallowtails of the season as they fly against the red canyon wall of the North St. Vrain river near our home—two swallowtails following the water’s course, taking summer with them. But they are not the last butterflies of the season. These I spot on November 12, the day our members come to the barn to pick up their Thanksgiving vegetable shares, a day with temperatures in the seventies that we might call “unseasonably” warm, except that word makes less sense now as the weather becomes increasingly unpredictable.

“Welcome to another beautiful day of global warming!” a friend calls from the barn. We haven’t had rain or snow for over a month; if it weren’t autumn, we might even call it a drought. Later that day I notice two sulphur butterflies, so dainty and yellow, I might have missed them against the dried grass if their movement hadn’t caught my eye. With winter approaching, I imagine they’re on their way to a warmer place. Then I realize butterflies can no longer be called summer birds—with a warming climate, November in Colorado has become that warmer place.

On one of those warm autumn days, my grandson and I are jumping on the trampoline at our farm when he notices a tree seed on the trampoline’s surface. He picks it up to show me: “I found a butterfly wing.”

“It does look like a butterfly wing,” I say, “but it’s a seed pod from a tree.” I split it open. “See, here’s the seed inside. It acts like a butterfly wing by helping the seed get carried by the wind so it can be planted far from the tree.”

We pick up a few others and wonder which of our many big trees near the trampoline has dropped it: willow, chestnut, ash, or elm. Later I find out it is a maple seed that must have blown a long way to find our farm. How exquisite a system—and how vulnerable—that depends on wind or rain or sun to sustain it. In the eyes of a child, each small part raises questions of wonderment, a bewilderment of nature we can only attempt to explain, even as it changes in ways never witnessed by humans before.

Reaching across generations, Maria Sibylla Merian teaches the importance of paying attention to the smallest of things, while in her ecological portraits, she portrays how small things fit together to create a more intricate whole. By focusing on the minute and mundane, piece by piece, step by step, a new world of wonder emerges. May Maria Sibylla Merian’s ecological vision help us protect the world of butterflies spinning and turning like seasons still changing before our grandchildren’s eyes.

Notes

This bibliography has been compiled from research available in English or translated sources only; I have not consulted sources in other languages.

[1] See Reisma, 19.

[2] Merian, Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam. Translated Rucker and Stearn. Quoted in Heard, 9.

[3] Merian, Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam. Translated Rucker and Stearn, 72. Quoted in Etheridge, “Metamorphosis of Natural History,” 19.

[4] Merian, The New Book of Flowers. Klier translation, 14.

[5] On Joachim von Sandrart see Reitsma 20; 23.

[6] Merian, The New Book of Flowers. Quoted in Schmidt-Loske, 10.

[7] Merian, Caterpillar I. Quoted in Thomas Burger, The New Book of Flowers, 17.

[8] Todd, 75-76.

[9] On Merian’s reference to her “entirely new invention” see Wettengl, 58, and Todd, 74, on the life-cycle; Schmidt-Loske, 18, and Wettengl, 25, on the magnifying glass; and Reitsma, 75, on the microscope.

[10] On Merian’s commentary on berries used for abortion by slaves in Surinam see Reitsma, 194, and Todd, 180.

[11] On the Native woman accompanying Merian on her return from Surinam see Reitsma, 205.

[12] Merian, Metamorphosis. Quoted in Todd, 129, and Etheridge, “Metamorphosis of Natural History,” 19.

[13] Merian, The Caterpillar Book. Quoted in Todd, 223.

[14] For the defense of Merian in the Eleventh Annual Women’s Rights Convention report see Todd, 248-249.

[15] Reitsma, 15.

[16] On the naming of this butterfly for Merian see Schmidt-Loske, 132.

[17] Merian, Caterpillar I. Quoted in Burger, 21.

[18] Merian, Caterpillar I. Quoted in Wettengl, 67, note 40.

Sources

Brafman, David, and Stephanie Schrader. Insects and Flowers: The Art of Maria Sibylla Merian. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008.

Engle, Margarita. Summer Birds: The Butterflies of Maria Merian. Illustrated by Julie Paschkis. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2010.

Etheridge, Kay. Maria Sibylla Merian and the Metamorphosis of Natural History. Endeavor 35.1 (2010): 15-21. Available online. Accessed 1-4-17.

Etheridge, Kay. “Maria Sibylla Merian: The first ecologist?” In Women and Science: Figures and Representations - 17th century to present. Donna Spalding Andreolle and Veronique Molinari, editors. , Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011. 35-65. Available online. Accessed 1-4-17.

Heard, Kate. Maria Merian’s Butterflies. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2016. All quotations in this book are from Rücker and Stearn.

Husley, Robert, ed. The Great Naturalists. Thames & Hudson, 2007, London: The Natural History Museum: 118-123.

Merian, Maria Sibylla. Butterflies, Beetles, and Other Insects: The Leningrad Book of Notes and Studies. Edited and with an introduction by Wolf-Dietrich Beer. N.P.: McGraw Hill International, 1976.

Merian, Maria Sibylla. Der Raupen Wunderbare Verwandelung/The Wonderful Transformation of the Caterpillar. Part I. Nuremberg, 1679. No English edition available.

Merian, Maria Sibylla. Neues BlumenbuchI/New Book of Flowers. With contributions by Thomas Burger. Munich; London: Prestel, 1999.

Merian, Maria Sibylla. Neues Blumenbuch/New Book of Flowers. Edited and with an introduction by Melanie Klier. Munich; New York: Prestel, 2003.

Merian, Maria Sibylla. Der Raupen Wunderbare Verwandeling/The Wonderful Transformation of the Caterpillar. Part II. Frankfurt am Main, 1683. No English edition available.

Merian, Maria Sibylla. The St. Petersburg Watercolors. Edited and with an introduction by Eckhard Hollmann. With natural history commentaries by Wolf-Dietrich Beer. Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2003.

Merian, Maria Sibylla. Leningrad Watercolours. Edited and with an introduction by Ernst Ullman. GDR: Edition Leipzig and C. J. Bucher, Ltd. 1974.

Merian, Sibylla Maria. Insects of Surinam. Cologne: Taschen. 2009. Edited and with an introduction by Katharina Schmidt-Loske. Based on the copy owned by the Offentliche Bibliothek, Universitat Basel. English translation by Joan Clough.

Merian, Sibylla Maria. Der Rupsen Begin/The Caterpillar Book. Part III. 1717.

Merian, Sibylla Maria. Erucarum ortus, alimentum et paradoxa metamorphosis. Amsterdam: Ooesterwyck, 1719. Staatsbibliothek Bamberg facsimile available online. Accessed 1-12-17.

Reitsma, Ella. Maria Sibylla Merian and Daughters: Women of Art and Science. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008.

Rice, Tony. Voyages of Discovery: A Visual Celebration of Ten of the Greatest Natural History Expeditions. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books, 2008. (First created by Co & Bear Productions, UK, 2008). 90-119.

Rowland, Ingrid D. “The Flowering Genius of Maria Sibylla Merian.” The New York Review of Books. April 9, 2009. Available online. Accessed 1-19-17.

Rucker, Elisabeth and William T. Stearn. Maria Sibylla Merian in Surinam: Commentary to the facsimile editon of ‘Metamorphosos Insectorum Surinamensum’ (Amsterdam 1905): based on original watercolors in the Library of Windsor Castle. 2 vols. London: Pion, 1980-1982.

Schmidt-Loske, Katharina. “Maria Sibylla Merian’s ‘extremely costly’ journey to nature’s treasure-house.” Introduction to Insects of Surinam by Maria Sibylla Merian. 7- 20.

Stearn, William T. “Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) as a Botanical Artist.” Taxon, vol. 31, no. 3, 1982, pp. 529–534. Available online. Accessed: 1-9-17.

Swaby, Rachel. Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science—and the World. NY: Broadway Books, 215. 47-50.

Todd, Kim. Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis. Orlando, FL: Harcourt, 2007.

Valiant, Sharon. “Maria Sibylla Merian: Recovering an Eighteenth-Century Legend.” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 26, no. 3, 1993, pp. 467–479. Available online. Accessed 1-9-17.

Wettengl, Kurt, editor. Maria Sibylla Merian: Artist and Naturalist, 1647-1717. English translation by John S. Southard. Frankfurt: Verlag Gerd Hatje, 2008.

Wulf, Andrea. “The Woman Who Made Science Beautiful.” The Atlantic, Jan 19, 2016. Available online. Accessed 1-12-17.

Kayann Short

Kayann Short, PhD, is the author of A Bushel’s Worth: An Ecobiography (Torrey House Press), a Nautilus Green Living & Sustainability winner. Her work appears in Midwest Review, Hawk & Handsaw, Pilgrimage, Dash, Mad River Review, and the anthologies Dirt: A Love Story and Rooted: The Best New Arboreal Non-Fiction. She founded the Friedman Feminist Press Collection at Colorado State University and farms, teaches, and writes at Stonebridge Farm on Colorado’s Front Range. More on her work with ecology-based memoir can be seen at www.ecobiography.com. Her essay, “Food for Bears,” appears in Issue I of The Hopper.