Fiction

From Issue III (2018)The Serpent

by AMY WELDON

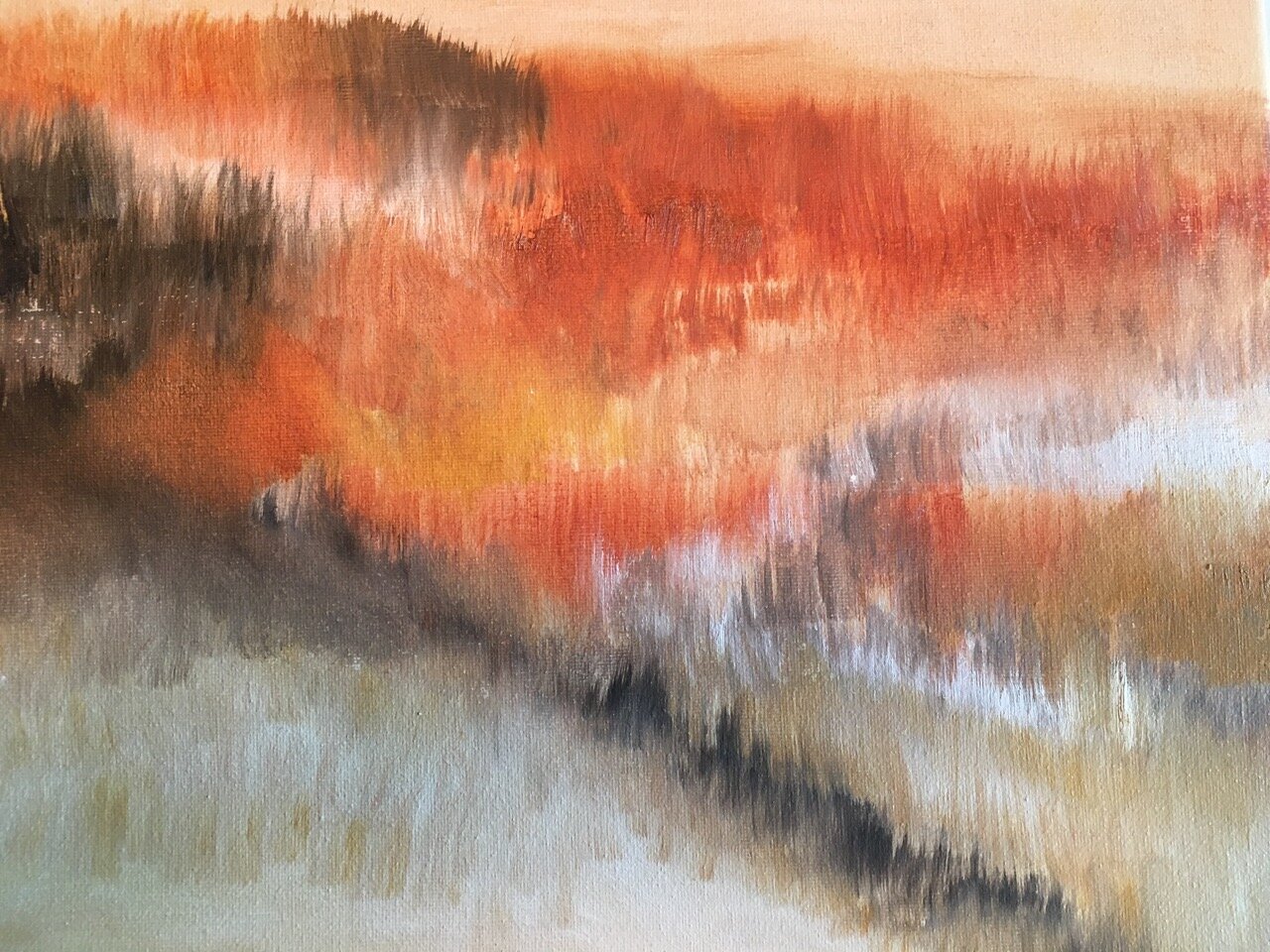

Fire Behavior | JUDITH SKILLMAN

Oil on canvas, 14 x 11 in., 2018

Genesis / Proverbs 31

He left her alone in what used to be their garden, with blackberry brambles clotting the fencerows and all the animals bawling to be fed. All winter he’d drunk and raged and watched her. She’d spent whole days hunkered there next to his sleeping couch, her hand limp in his fists. The jars on the pantry shelves and the smokehouse hams diminished: three, then two, then one. When February dawned, bright and cold, he wobbled away down the red dirt road with his knapsack on his back, his clay-colored hair bristling. You’ll never survive here without me, he shouted back at her. Every move you make will be in pain. Never, once, could she have dreamed that she’d be glad to see him go. But left alone, she could put the garden back the way it was.

So she took stock. The tin roof on the house: still good. The well still drew; the fig tree and the plum and peach trees were setting bloom and leaf. The vegetable patch, however, had that sunken, scraggly look a garden gets when a woman has her mind on something else. Rickety wooden winter-bleached tomato frames still cradled brittle white vines, where a few cold-leathered orange fruits still clung. Blue-gray collards burst up into yellow flower. Pepper plants were smashed flat where some creature had rummaged through. A possum had laid waste one last melon over by the fence, its striped hull cracked and teeth-raked, its faded heart laid bare. At least the deer fence, ten feet high, was still intact. The metal discs he had cut to scare them still shimmered and bounced in the wind. An evil little face was etched into each one; they’d done that together, laughing, charming a protection for their food against the crows and deer and dangers threatening this garden that would surely feed them both together for all time.

Without him, the milk cow lost a tendency to kick. The chickens clustered back around the house. The big yellow cat came out from under the porch. She replanted the seeds, upright in their twists of brown paper. Ole Timey Blue. Cow Horn. Cherokee Purple. Trail of Tears. Arkansas Traveler. Mortgage Lifter. Hill Country Red. Yellow Gold. Moon and Stars. She ripped out the old tomato vines and the tall fierce weeds and hauled them to the place where the other garden skeletons were melting down to next year’s food. She stropped the razor and sharpened the scythe and swung it through the high grass to cut it all around the house, the garden, the fig tree. Because in the warm weather coming on, snakes would be moving.

He had hated snakes beyond reason, ever since he opened the chicken coop and found a brown-and-gold rat snake stretching its mouth open around a fresh white egg. Don’t bother them and they won’t bother you, she’d argued. They keep the mice away. She’d stopped up every hole in the coop and reburied the fence wire and thought that was the end of it. But in his bad time, as the grass feathered high and the garden grew wild and then withered and the chickens got feral and experienced, she came to fear what might be out there: the panicked muscle writhing to life under her foot, the hot needle to her calf. Overgrown and wild and forlorn, this was not the happy garden they’d been given anymore. She’d die out here, no one to bury or to mourn her.

But now, on a summer morning, the first tomato-ripening heat just taking hold, she lets herself release those fears. The garden is hers again. The seeds are up and flourishing. The melon-hills are crowned with glory, the beans climbing their cornstalks right on time. Green baby crabgrass bristles between the new collards and the lettuces. If she lets crabgrass go, she’s in for a war, gripping giant clumps of it and heaving it out. Gripping is a problem for her now. At night her hands ache, down in the joints. So big-knuckled and rough they are, so different from the slender fingers she held up before her own eyes as a girl, marveling This is my body, all of this is me. Deep in her hip is a grinding of bone on bone that freezes her in place, howling, if she catches it wrong. So she stretches and she takes a rest and she tries to ignore the way her body is no longer fully hers. Traitorous and tired, it’s been swelled and split by both her sons. The one son’s dead. The other—she doesn’t know where he is. It’s a pain worse than her swollen hands to think on them. So she chooses the pain that feeds her. She rubs the pig fat against her joints at night to keep them as supple as they can be for the next day in the garden. For a woman, keeping herself fed in this world is a full-time job. And now there’s only her, out here at the end of the world, to see to it.

She chops the young crabgrass with her hoe, turning the roots over to bake in the sun. Then something rustles in the squash vines, slow, low against the ground. She freezes. There’s only one thing that sound can be. But she can’t just back away or it’ll find her sometime she’s less ready for it, like when she’s barefoot on the porch steps, walking out into the yard at night to see the stars. This is her garden. She has to be free to move in it.

She steps back and slams the hoe into the soil. I tell you to come out. The air thickens with a heavy liquid hush of skin on skin. She chops the dirt. Come out. Slowly a rattlesnake unfurls itself into the light. Black birdwing shapes on its back, bird after bird after bird, loop toward her in the dirt. Its thick midsection is as wide as her right arm. Its black tail ends in a long cluster of rattle-beads. Its head is as big as her own outstretched hand, fingertip to wrist. And its lidless eyes are open, watching her.

Cold fear shoots down her spine, locking her to the dirt. Words scramble in her head: be still, it’ll strike, oh why oh why did— She stares at the flat spade-shaped head and marshals her lost man’s counseling words: big snake is less to be feared than a small one, big snake knows what to use his venom on, little snake’s just like a shirttail boy, lash out at anything he can. Wild shirttail boy. Lost son. So much fear and grief now all undone in her. Why, oh, why did she command this beast out into the light?

The black eyes watch her. Snake venom takes away the joint pain. Whose voice is this? Sure it does. Longing rises in her chest, coloring the fear like wine in water. No more pain. Dizzily she pictures it. Step forward. Grasp this rope of muscle around its throat. Slip her right hand underneath the belly scales—it will be heavy—and lift it toward her heart. The flat eyes stare through her at nothing. I’ll be still. Where is that voice coming from? You’ll pick me up and I’ll be quick. Just one little bite. You won’t hardly feel it. And all your pain will then be gone.

Inside a pure cold emptiness opens, waiting, humming like her lost sons in their sleep. It is the place from which fear reaches for her in the night. The space in which her thoughts chased around and around as her lost man gripped her hand between his own. It is not-knowing. It is intolerable. It is inescapable. It is where she must live now, on her own. She cannot run. And the doing and the caretaking of each day—the clothespins on the line, the sharp edge of the blade against the dirt, and the red skin of the fruit her own hands have brought forth—is the sturdy warm force that sends the fear back into its hole.

She lifts the blade and swings it down. The big snake bunches backward in a self-protective coil, rattle-buzz slicing the air. It’s not a hiss, it’s a harder sound, silver-edged and mean. Mean? Afraid. All down its neck is a split in the black-and-tan scales her blade has opened. It’s bleeding. It is red meat and nerve and hunger, like any other thing.

She steps back and the rattlesnake whips away under the wide sunlit leaves. The fence quivers as it hits what must be a hidden hole, back there, in the wire. It’s out in the pasture now, seedheads swaying as it passes. With her hoe upright in her hand, she stands and watches it. Rustle, rustle, away and out of sight.

Amy Weldon, a native Alabamian, is professor of English at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, and the author of The Writer's Eye (Bloomsbury, 2018) and The Hands-On Life (Cascade, 2018). Her essays, short fiction, and reviews have appeared in Orion, The Common, About Place, Los Angeles Review of Books, and a variety of edited collections. She blogs on sustainability, spirit, and self-reliance at cheapskateintellectual.wordpress.com.

Judith Skillman

Judith Skillman is interested in feelings engendered by the natural world. Her medium is oil on canvas and oil on board; her works range from representational to abstract. Her art has appeared in Minerva Rising, Cirque, The Penn Review, and The Remembered Arts. She studied at the Pratt Fine Arts Center and the Seattle Artist League. Her website is jkpaintings.com.