Nonfiction

From Issue II (2017)The Whole of the Moon

by MELYNDA FULLER

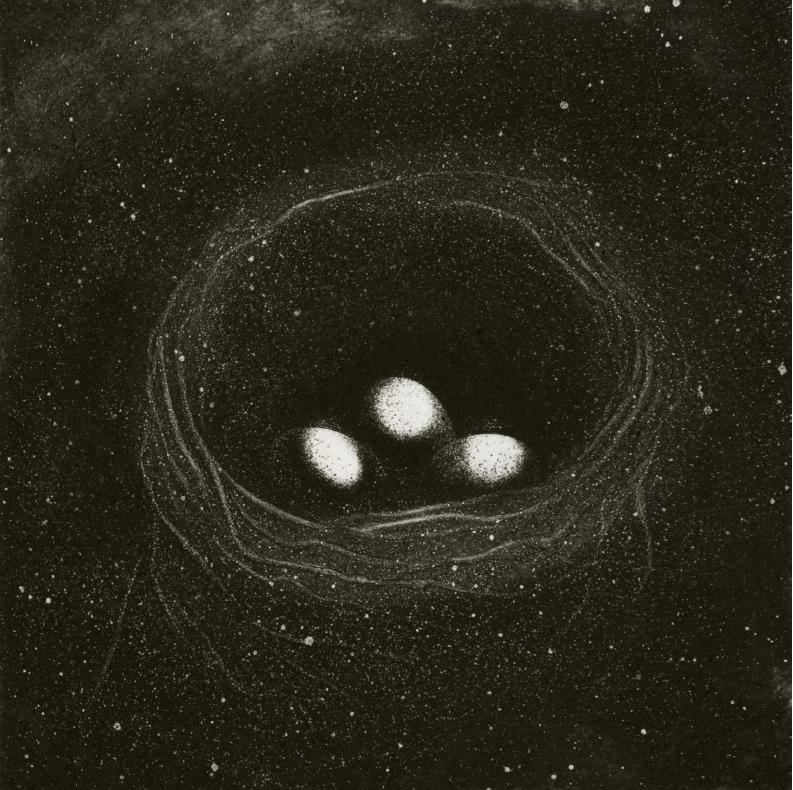

Nest | BRIAN D. COHEN

Etching, 5 x 5 in., 2016

I.

I see Jupiter’s moons and the surface of our own satellite for the first time in New York City. As I leave work for the day, looking out the seventh-floor window by the elevator in my office building, an almost full moon rises above Union Square in a moment altered through the centuries only by the architecture of the city. The moon has always hung brightly in that patch of sky. After a few avenues, I arrive at the High Line, a park built on elevated tracks left over from trains long forgotten that runs along the Hudson in Lower Manhattan, just as the sun disappears behind New Jersey in the middle of October. I argue with myself, trying to decide whether it’s twilight or dusk. I’ve forgotten the definitions.

The park is a strange one. Wooden lounge chairs sit back a few paces from the flow of public traffic on beds of smooth stones; as I sit on one of the chairs, I see an idea of nature in front of me, one I assume is supposed to make me forget the idling truck one story down on the street beneath the boardwalk, the crying child walking with her mother, the glaring W atop a hotel in Jersey City. There are people sitting on either side of me, two men to my left, one to my right, and all are texting on their phones. I watch them instead of the sunset for a moment.

What I see at the park if I look straight ahead with a sort of tunnel vision is the following: the Hudson River and the tops of yachts sailing up and down it, some with strings of white lights, some more subtly lit; the darkening sky where the sun was moments ago, the clouds now much closer to the color of rose tea than cotton; the landscaping of the park, meant to imitate the tops of sand dunes along the ocean’s shoreline. Tall, thin reeds are bedded with cattails and bushes with large flashy leaves. Two trees with thin, long whips of greenery frame the scene. For a moment, I attempt to believe this story the artist is telling me: that I’ve left city limits behind and I’m with nature now. But, just as I do, a tall blonde woman snaps my picture.

Stars begin to appear in the sky minutes before seven. That’s what I’m here to see, the stars, or more precisely the planets. I had made it to the end of my twenties without looking at the sky through a telescope, or a lens of any sort, really. Months earlier, I’d heard about a group called the Amateur Astronomers Association that meets at the High Line every Tuesday, and I was finally joining them.

II.

I moved from western Pennsylvania to Brooklyn immediately after college, steaming down the turnpike as quickly as I could, away from there, propelled towards here. But I miss the open landscapes and sunsets I took for granted as an adolescent in a more rural part of the country. I have lived in seven different apartments in the city, none with a clear view of the horizon. In one, I had access to the roof where I often watched the sun set behind Harlem. Two other spaces changed colors indoors, the light bouncing off the pieces of furniture in my bedroom, transforming them from glaring white to subtle pink to hazy blue, reflecting what was going on outside. Only when I spend a weekend at my parents’ house in Pennsylvania do I once again see the sunset in Cinemascope. Some people credit the brilliance of the skies in this area of the country to pollution left over from the steel mills. It’s actually the purity of the air that allows the sky to become so deeply hued.

If I time my travels right, I see the sunset just as I reach my favorite silo on the drive to my parents’ home. I’m not certain if the silo is the first I pass on my way home, but it’s always the first I notice. It sits on a hillside along a major highway that cuts through the landscape. The highway wasn’t always here. I try to imagine the faces of the house’s owners first hearing the news, that just beyond their front yard, the sloping hill would be bisected by tar, asphalt, gravel, and eventually eighteen-wheelers, tour buses, hybrids, SUVs. Workers broke ground for the interstate in the 1950s and I’m certain the farm existed first; the wooden siding on the house shows that kind of wear. The barn, situated beside the silver silo, is well cared for, its wood stained a deep brown. A Pennsylvania Dutch hex sign in the shape of a starburst, matte reds, blues, and yellows filling in the slightly rounded triangles of each arm, hangs dead center on the structure’s face; its astronomical shape symbolizes good luck.

It’s usually at that moment, the few seconds when this part of the landscape fills my sight line, that my city persona, the one tied up in schedules and image, begins to fade and I loosen my speech a bit as I sing along to the radio, a slight twang finding its way back. I allow my thoughts to drift to the landscape rather than new acquaintances, a missed party, career concerns. I’ve heard this place described as somewhere that isn’t of the North or the South and now find myself in a similar limbo. Living between two worlds, the one I was born into, a rural life where I never found my place, and the adult life I’ve built in New York, requires the ability to morph.

In New York, I cling to this image, this mental snapshot of the sun striking the farm at sunset. I picture the small stone house appearing just as I emerge from an extra-lengthy overpass, the silo sitting downstage, a parked pickup truck stage left, a shed at stage right. On a later drive, days after I’ve described this very scene to a friend, I search for that small moment as I speed down the interstate. The house isn’t precise; the silo could be one of many. Pieces of my snapshot are real—a yellow stone house here, a silo identical to my dreamed one there—but I’ve romanticized the scene with no visuals to prove or disprove what I’ve experienced.

III.

On this October evening in New York, it’s Jupiter that I can see shining brightly next to the almost full moon. As the sky darkens, those images that are hidden during the day, televisions flickering from a condominium window along the High Line, faint constellations above, become visible. I’m at once drawn to the smallest moments of human existence: relaxing at the end of a workday, the action of TV dramas bouncing their light off still walls, and our very point of origin, the solar system.

As I walk to the meeting place of the astronomers, I can see a busy figure adjusting a large orange electronic telescope. A crowd of people has already gathered. You can make it to the moon in seventy-two hours, but it takes about four and a half years to get to Jupiter, one of the astronomers is explaining to a visitor, as if this is a possibility. A man and a woman whom I assume to be in their early forties look through the telescope, which is fixed on the moon, first. What tha hell? the woman cries, as she jerks her head away from the eyepiece. You gotta come see this, she says to her companion. He looks through and responds similarly. Then before he can say anything more, she adds, holding binoculars to her face and turning around towards the water, And if you look across the river you can see Jersey! Look, you gotta see Jersey, too! As if on reflex, we all look across the river at New Jersey.

When it’s my turn to look through, I tell myself that I’ll stay calm, act like I’ve done this before, but I can’t. That’s incredible, I say loudly enough for most of the crowd to hear and to warrant a smile from a shy, aging astronomer named Robert who’s manning the telescope. Isn’t it, he replies. The surface of the moon looks exactly as it has looked in every photo I’ve ever seen: mottled white with dark craters, a little rough at the edges, a dead rock so bright it stings my eye a little to look at it for too long, suspended in the sky.

The crowd grows as Robert turns the telescope to Jupiter. The four Galilean moons, Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, glow around their mother planet, and the bands of its surface bleed into one another, deep beige, burnt sienna, and soft pink. My reaction is the same to this view. And I want a photograph of this moment.

IV.

My parents call in mid-March.

Hello Melynda, my mother says on the message. You’re probably already out for the night, but we wanted to tell you that tonight is a supermoon. It’s the biggest it’s been in, what was it Dick?—she pauses to wait for my father’s response—eighteen years.

I call her back. I’m not out for the night; I’m in my tiny studio apartment plotting an escape, to where I’m not sure.

Do you remember when Dad and I took you and your sister out to the lake? she asks. She didn’t remember it until my father told the story; I have no recollection.

I want to drive to the ocean to see the moon and use the high-powered binoculars my parents gave me for Christmas, but I always seem to pause, whether it’s an impulse to watch a meteor shower, see darkness, or just hear the ocean that’s overtaken me. Fear of isolation, of the blackness, terrifies me, not a fear of leaving people behind, but in encountering them out there, far away from stacked apartment living and street lamps. This is an instinct I can’t shake from my rural past.

And I can think of no one to call with whom I’d want to share that moment with the moon. I take a walk around the park by my house, using my binoculars where the moon peeks out of the trees. I call my mom back; I call a faraway friend. I dodge couples walking teacup varieties of fluffy dogs and already drunk men on their way to the corner social club. I’m sorry I didn’t drive to the ocean.

V.

This woman, Terry, at the end, says Robert, she has the best view of the moon. I walk down the row to find her, realizing along the way that she’s the only woman with a telescope along the High Line. An older man, maybe seventy or so, is looking at the moon when I get to her. He asks how far away it is. 250 million miles, she answers back. Oh wait, stop, that isn’t right. I’m so used to giving distances in billions. The moon is only 250,000 miles away. I look through next and see the entire moon, not only the edge, in high definition.

I also see Uranus. Maybe. Alan, whose telescope is fixed on the planet, tells me it’s difficult to know for sure if that’s what we’re looking at because it’s so distant, only a speck of light in the lens. But to see Jupiter and its moons, plus Uranus, on your first time out, he says to me, Well, that’s just luck. Alan’s telescope is programmed to locate the planets; he finds them by remote control.

Here, use these and just see. You’ll be amazed. I am about to leave, but another astronomer, Larry, stops me and tells me to look at the moon through his binoculars. I do and it looks perfect with even the shadow of its last unlit crescent visible. It feels three-dimensional, I say. It doesn’t just look three-dimensional—I can feel it.

Those are the moments, he says, moving his hands toward the sky with the grace of a composer, when you see it through the lens and suddenly, he makes a whooshing sound and moves his hands along his head, you’re there. His eyes get a little wider as he does this and he casts them up toward the sky.

Alan cuts in from a few feet away. Hey Larry, do you know the distance to Jupiter? Larry responds, I think it’s around four hundred million, but I’m not sure. He adds the distances to Neptune, Pluto, and Mars, then he turns to me and says, It’s not until you really think about those distances, what they mean, that you realize what you’re looking out at. You’re looking millions of miles out into the solar system.

I’ve contemplated this thought while watching the sun set, the idea that I don’t always think about what I’m witnessing, that the setting of the sun is actually a violent game of tug-of-war between the sun and the earth taking place over tens of millions of miles, gravity being the thick rope connecting the two. But tonight his words carry a heft, sound as a warning, perhaps, as I feel an obsession with the stars sparking and spreading in my head.

I tell him about a story I read once. It was about the first land plants, the fact that had the earth not made itself hospitable, allowing plants a chance to find their roots on land, we wouldn’t exist. And then we’re talking about life, how life begins, the moment when life first began, how he and I arrived at this moment with telescopes and binoculars, Jupiter’s moons and our own. He pushes the tips of his middle fingers together, hard so that they flatten against each other. There had to be this first moment, when the inorganic becomes organic, he says. We have theories about lightning striking; now there’s energy and things begin to move; but what is that moment? How do we even describe it? Maybe we arrived on a chunk of rock from out there. Who knows?

I don’t.

VI.

When you see the sun begin to disappear, resist the urge to document it. Do not capture this moment on film, this moment when the sun sets and the stars and planets, beginning tonight with Venus, begin to appear above in the darkening sky. Remove the camera from your face, watch with your eyes rather than through the miniature plastic of the viewfinder. Look out over the horizon.

The sunset as fetish object.

I want to turn to my companion as we sit near the edge of the Grand Canyon and say these words to him. The camera he holds covers most of his face and with each click the sound of the motors inside fills the space around him, mechanical noises of gears advancing film and shutters opening and closing. I want him to look up, to notice the variegated colors of the clouds, the purples, the magentas, the shadows of bluish-gray, the occasional shock of pale yellow. Then look over the canyon. See the way the layers of limestone, sandstone, and shale mirror the colors of the sky, the midnight-blues near the canyon’s bottom, the sharp maroons and burgundies closer to the horizon. He and I are compatible travel partners, but it seems that in these, not moments but experiences, we always miss each other’s point. I don’t say anything. I move to a rock a few feet away where the clicks are less noticeable. As the sun falls behind the flat line of the desert, a wind blows up from the canyon, the Colorado River is no longer visible, the temperature drops suddenly, and I need a sweatshirt.

We leave the park in darkness, almost hitting an elk, its posture that of a flying reindeer as it dives in front of our car.

A few weeks later, when the film has been developed, he and I spend an evening drinking wine and looking at these pictures from our trip through the Southwest. When my parents come to visit we show them a digital slideshow on our television. Afterward, all are packed away: the film prints in a box in the closet, the digital images on a hard drive. I can still feel the wind that blew over my body.

Melynda Fuller

Melynda Fuller’s essays and criticism have appeared in The Rumpus, Bust, A Women’s Thing, and Poets & Writers, among others. She received her MFA from the New School and is currently at work on a collection of essays.

Brian D. Cohen

Brian D. Cohen is a printmaker, painter, educator, and writer. In 1989, he founded Bridge Press to further the association and integration of visual image, original text, and book structure. He has shown his artist’s books and prints in over forty individual exhibitions, including a retrospective at the Fresno Art Museum, and in over two hundred group shows. His books and etchings are held by major private and public collections throughout the country. He was first-place winner of major international print competitions in San Diego, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC. His essays on the arts and education are found in Art in Print and The Huffington Post.